UCL Module. 0.1 Situating our perspective: Transformation.

Intro to 'situating our perspective'. Claim: The only viable story of the future is transformation.

This short SubStack series gives a weekly key insight from the Masters module I co-teach on 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business'. You can see them all here. The Atelier of What's Next WeekNotes continue in parallel.

This week:

Introduction to 'Situating our perspective'

Claim: The only viable story of the future is transformation.

Introduction to 'Situating the module's perspective'

As part of the first lecture, we give our framing viewpoints on the domain covered by the 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business' module. These are the 'red threads' which run throughout the lectures, and were fundamental in us choosing what to teach, the essay questions we set and so on.

As such, they are so important to the rest of the module that I am going to lay them out in full. This post considers the role of transformation. The next has three claims about sustainable business. In future posts I will only pull out one or two items from the lecture.

One thing we emphasise when giving these perspectives it that the students can have a different view. We have come to these conclusions based on our own work, plus our understanding of others' research findings. But that doesn't mean that they should be treated as completely right or uncontestable.

We think that being clear on our assumptions is fundamental to good teaching (and good research, and quality efforts at change too, for that matter). It is more honest of us to say to the students (and you, as our readers) the foundation on which the module stands. That allows you to form a more rounded judgement on the whole module, and to challenge us, if you so wish. (It is also us modelling to the students the importance of 'showing their working', which we will ask them to do in their essays.)

Claim: The only viable story of the future is transformation.

Jim Dator is noted futurist and former Director of the Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies. When he studied the many ways we talk about what is going to happen, he found that there were only four recurring stories of the future:

Continuation: business as usual, more of the status quo growth. The fundamental relationships, structures and dynamics of the situation continue. The whole ensemble just gets bigger.

Limits and discipline: behaviours to adapt to growing internal or environmental limits. The

Decline and Collapse: system degradation or failure modes as crisis emerges.

Transformation: new technology, business, or social factors that change the game. Post-transformation ‘growth’ is different to status quo growth.

An example of transformation would be the industrial revolution. This short paragraph cannot do justice to the complex set of processes drove a shift from agrarian to industrial societies, starting in England. It is called an industrial revolution, and it certainly profoundly changed the structure of the economy. But the changes played out at more than an economic level. How people lived, where they lived, how they interacted with each other, who had power, how politics was organised -- all of these changed over a period of decades.

The industrial revolution changed not just the economic layer, but the 'full stack' of layers, including power, culture, and down into fundamental beliefs about the nature of the world and humankind’s place in it.

At the time people were aware something profound was happening (read almost any Dickens). But they didn't know where it was headed. And someone in 1700, say, would have found it almost impossible to imagine the world of 1900. The arrangements after the transformation are so profoundly different from the previous norms, that they are almost inaccessible to the people who came before.

Let's take Dator’s model as good-enough for understanding what stories of the future are available to us now. (And, yes, all models are wrong, but some models are useful.)

Our view, as expressed in this Module, is that:

1.More Continuation will inevitably lead to some serious form of Decline and Collapse.

That was the message of IPCC Special Report on 1.5C. It is the conclusion of many scientists.

Our current form of society has improving quality of life for people only by having an increasing throughput of ever more materials and ever more use of energy. In its current form, that relies on treating nature as an infinite source of materials to draw from, and an infinite sink that can cope with all of the waste that is produced.

But the natural processes of the Earth are not infinite. They have thresholds beyond which they start to change, then to decline in performance and, eventually, collapse. Each of those stages affect human society. The economy is, after all, a wholly owned subsidiary of the nature. If we continue as we are now then there will be decline and, eventually, collapse.

Yes, there are great technological innovations here or in the pipeline which can make a huge difference. So, some people argue that if we orientate our current system to prioritise technological innovation then we can avoid collapse with only a tweaked version of the status quo. In this view, we don’t need a political revolution, or a cultural revolution, only an industrial one.

We would find that argument convincing if humankind only faced one crisis, for instance climate change. But there is also the crisis of biodiversity loss. That points to deeper causes, requiring deeper changes.

Also, the argument would be more convincing if addressing climate or biodiversity crises required technologically easy changes in relatively small or peripheral industries. That can be true of single issues. Key example: the hole in the Ozone layer. Scientists spotted it. Countries negotiated a treaty, through the UN. Technological innovations were rolled out on aerosols and refrigeration. All of that in the face of industry resistance, at least to start with.

But the changes need to address the climate and biodiversity crises are of a different kind. The burning of fossil fuels is fundamental to a modern economy. The technological changes are not about swapping out one widget for another. The incumbent sectors are crucial to regional economies, and have great political power.

These crises are not the result of one-off bad luck on atmospheric chemistry. They are the result of a fundamental feature of the status quo, which cannot acknowledge, or operate within, planetary limits.

2. Limits and discipline will not be stable or enduring.

For some people the only way forward is to impose the planetary limits on global societies and economies. This view often goes under the umbrella term of ‘degrowth’. The general idea: it is possible to use government policies and regulations internationally to transition to a functioning economy where people have high standards of living with vastly reduced environmental impact and social injustice.

Now, degrowth is a topic which quickly triggers people. It has become a touchstone in an ever-more polarised debate. Our experience is that degrowth proponents see it as a test of whether you really get the true depth of the challenge facing humankind (and if not, you just don’t understand). The degrowth opponents see it as a proof of whether you get how an economy works (and if not, you just don’t understand).

Now, we find ourselves in the odd position of part-agreeing with both sides of that debate. We believe we understand that humankind needs to co-exist with nature, which isn’t possible with the current economy. We believe we understand that the current economy relies on growing value of activity. (It is worth bearing in mind that is true of the current economy in its current form. What if there was a different form? Hold that thought.)

Our point here is rather different from the polarised argument.

We don’t see how a world of limits imposed through government policies and regulation can be stable. How it can endure the bumps and disruptions of the real world. In short, how can imposed limits be sustainable?

We are heading to a world with over 9 billion people in over 190 countries. Even if many of the largest players accepted rules and discipline, it would not take many bad actors to free ride. International law did not stop Russia from invading Ukraine. What would stop Russia from keeping to producing oil and gas, and selling it on a black market? Or any of the other petrostates, which are currently very dependent on fossil fuels?

However desirable it is for global societies to exist within planetary limits, it is hard to imagine a pathway using limits and discipline which endures, especially in a world that is facing overlapping crises and emergencies, with lots of local and international pressure and conflict. Each of those is a potential trigger for escalation, which disturbs us out of whatever fragile international cooperation on limits has been established.

3. Therefore, transformation to new configuration(s) is necessary.

That leaves us with one plausible story about our future. Transformation.

If we are to have over 9 billion people to live their version of the good life, then we need global societies which have changed form (‘trans-formed’). The historical analogy is with the industrial revolution, with the ‘full stack’ of layers: economic, social, political, cultural and down into believes about the way the world works and our role in that.

Now, you may be thinking: well, isn’t transformation what the people who argue for degrowth want? Yes, but they see by imposing rules and discipline that all will follow. Our view is: even if you could adopt everywhere such international rules, the situation would fall apart under the pressure of events.

Instead, we are arguing that the necessary transformation will come from shifts in the internal dynamics of how most things work so. Rules and discipline are needed when those internal dynamics have not shifted, when continuation leads to collapse (point 1 above).

We are proposing a transformation where the internal dynamics of the ‘full stack’ (economic activity, our enmeshed cultural lives, political machinations and collective values-in-action) are sufficiently, and increasingly, aligned with natural processes, and human flourishing. In which case ,continuation of this new status quo does not lead to collapse. Imposed limits and discipline are not needed as the main way to stay sustainable (though there doubtless will be rules and international agreements).

Such a paragraph is easy to write (though, possible not that easy to read). But that doesn’t mean that transformation is easy to enact, or even imagine.

Just like someone in 1700, say, would have found it almost impossible to imagine the world of 1900, so someone in 2020 will feel bewildered and astonished by the world of 2200, or even 2100. The arrangements after the transformation will be so profoundly different from the previous norms, that they are almost inaccessible to us now.

There are some important differences to the industrial revolution. It was started in a relatively small location, took decades to move around the world, wasn’t being aimed at a particular ‘landing strip’, and was during a stable period for the climate. The coming transformation will need to be in many places around the world, happen much faster, be orientated to the planetary limits and social needs, and will be in a warming world (with the possibility of on-going destabilising climate events).

One thing we can be reasonably certain: there will be disruption along the way. Some form of decline in the status quo (and maybe part-collapse) is likely, and may even be needed, to make space and free up resources to go into the emerging status quo-to-be.

We don’t come to this conclusion happily or flippantly. Life would be so much easier if a revised version of the status quo was enough. We don’t under-estimate how hard the path ahead will be, not least because we have to make the path by walking.

Post Script

Since first giving this lecture, we have learnt that others have independently come to similar conclusions.

A very close parallel is

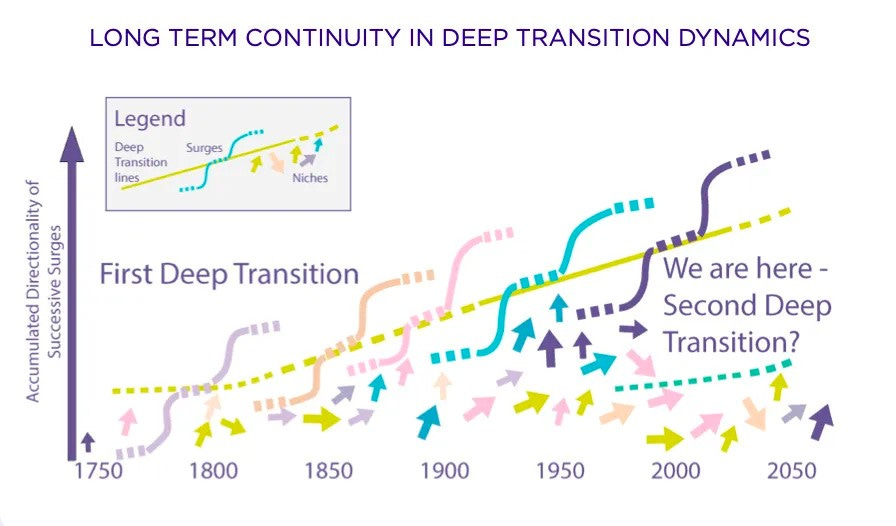

(in his brilliant newsletter, Just Two Things) who used Dator’s Four Futures model to come to the same conclusion – see his talk to mark a decade of the journal Futures here.Prof Johan Schott comes from the other direction, that of economic history rather than futures. He has concluded in this paper that the industrial revolution was the First Deep Transition and that we now need a second Deep Transition to reach a sustainable economy.

On the question of limits and discipline, in October David attended a lecture on postgrowth, where he challenged the speaker on:

1.How would any postgrowth economic activities out-compete currently existing economic systems?

2. How much can we know about the post-transformation world? If not much, how do we act now?

You can read more detail here.

Where we are in the ten lectures

Introduction -- here

0. Situating the module’s perspective:

0.1 The only viable story of the future is transformation. -- this note.

0.2 Three claims about Innovation and Sustainability in Business.1.Business Responses to the Sustainability Crisis.

2.Innovation Economics: Core Concepts and Issues (with a transformative lens).

3.New Product Development and Managing Technology Innovation.

4.(a) Sustainable Entrepreneurship and the route to commercialisation.

4.(b) Sustainable Finance.*

5.Innovation (eco)system – beyond the cult of the entrepreneur.

6.Sustainable innovation in a digital age.

7.Sustainability Strategy and Scenario Planning.

8.Transitions and The Bigger Picture.

9.Public Policy for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation.

10.Exploring Innovation and Sustainability through a Case Study.