0. Situating the module's perspective. 2. Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level.

A working definition of 'sustainable business' and 'innovation'. Claim: Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level.

This short SubStack series gives a weekly key insight from the Masters module I co-teach on 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business'. All those posts are gathered on this page. The Atelier of What's Next WeekNotes continue in parallel.

This week:

Reminder on ‘Situating the module’s perspective’.

A working definition of sustainable business.

A working definition of innovation.

Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level.

For completeness:

Beneath the jargon, innovation and sustainability in business is highly political.

We will see pockets generating a better future and cynical attempts to defend a failing status quo.

Reminder 'Situating the module's perspective'

This is the third in the series about the 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business' module I co-lead with Dr Will McDowall. And we’re still in the first lecture. How come?

Well, because the foundational assumptions of the module are important. That allows you to form a more rounded judgement on the whole module, and to challenge us, if you so wish.

There’s one more to go (this post) and then we will get into the specifics.

To remind you, this is what we’ve had so far:

Introducing 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business'. Does what it says on the tin, plus gives the titles of the ten lectures.

0.1 Situating our perspective: Transformation. Makes the big (and very contestable) claim the only viable story of the future is transformation.

A working definition of sustainable business.

You won’t be surprised there is no single, agreed definition of ‘sustainable business’. There are lots of reasons for this.

A young-ish field, finding its way. (Though we still don’t have a single, consensus definition of justice after several thousand years, so don’t hold your breath.)

Different definitions reflect the different values and assumptions of those making the definition (just like with ‘justice’).

Anyway, in the module we use a catch-all, which reflects our understanding of what a range of people across the field mean most of the time. The edges are a bit blurry. But, when people say ‘sustainable business’, generally they mean:

Private organisations (rather than a public body, like a government).

Those organisations are trying to make a profit (their revenues are greater than their costs). Historically, that has meant a motive of for-profit (=‘business’), but now some are for-benefit (≅‘social enterprise’). We’ll get to whether a business has to maximise returns to shareholders in the next post.

The scale of the organisation can be large (‘corporate sustainability’) or small (from start-ups looking to grow and SMEs happy to get by).

The scope of what topics are considered can be:

Single issue (eg Modern Slavery).

One domain (eg Environment).

The full waterfront (eg the Sustainable Development Goals).

A working definition of innovation.

Guess what? There is not one single, agreed definition of innovation. For the purposes of the module, we follow Joseph Schumpeter, who has a three-part definition of innovation:

Invention: origin of new ideas.

Innovation: introduction of novelty into the economic realm. Novelty usually means “new to the world” but sometimes is used to mean new to the firm or to the market.

Diffusion: adoption of novelties by others.

Yes, this is a little confusing because the working definition of innovation has a sub-part which is also called…innovation. Living languages can be messy like that.

The point: the ‘innovation’ covered in the module goes from having an idea, making the idea real and then taking that real expression of the idea out into the world.

Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level.

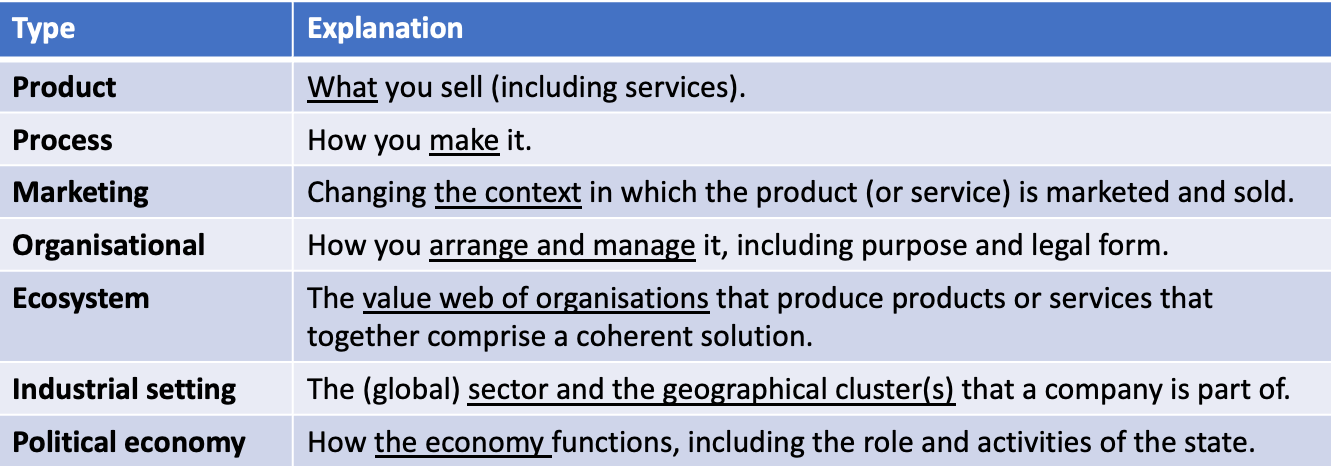

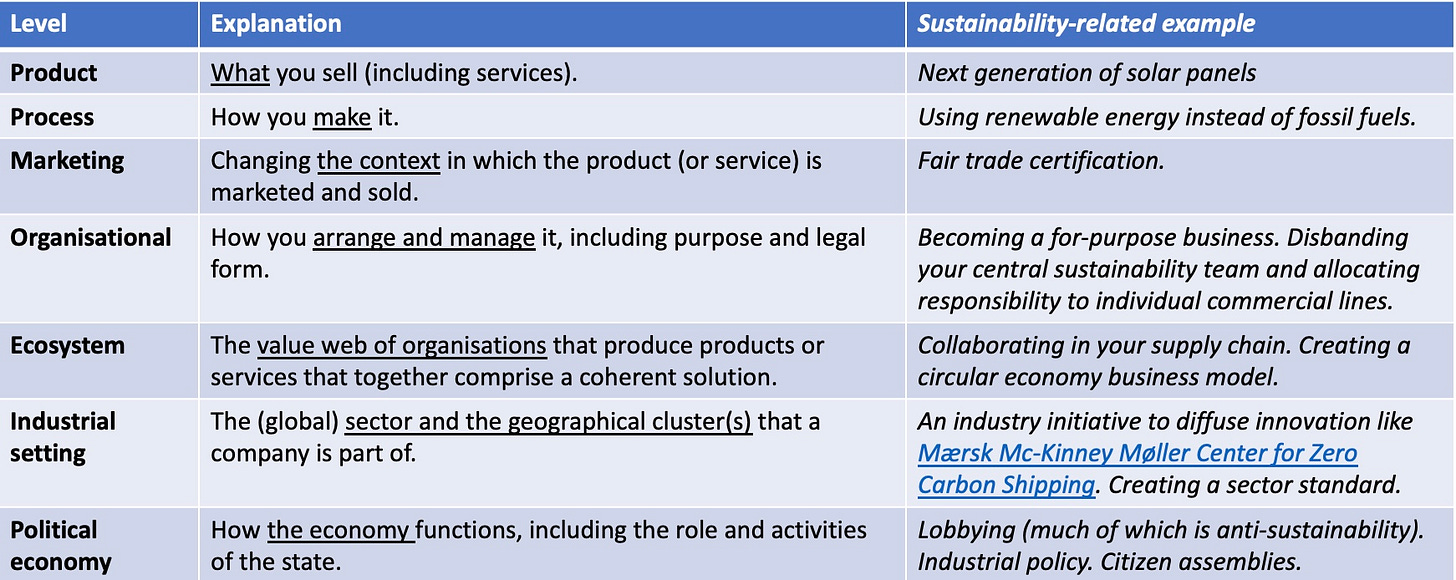

When we were drawing the Module together, we had an instinct that sustainability, innovation and business went together. But how to express that? We decided to build on the OECD Oslo Manual 2005 typology of innovation (note that subsequent editions revised this types).

The first four types are the most obvious:

Product. What you sell (including, slightly confusingly, services). A sustainability-related example: the next generation of solar panels.

Process. How you make it. Using renewable energy instead of fossil fuels.

Marketing. Changing the context in which the product (or service) is marketed and sold. Fair trade certification.

Organisational. How you arrange and manage what you sell, including purpose and legal form. Becoming a for-purpose business. Disbanding your central sustainability team and allocating sustainability responsibility to individual commercial lines.

Those four are from the 2005 OECD typology (though we have built out the ‘organisational innovation’ out from a more threadbare ‘how you manage it’). So, a normal, mainstream way of categorising innovations.

But we know from the research and our own experiences that there is more innovation (meaning: ‘invention, introduction and diffusion of novelty in the economic realm’) in sustainable business (meaning: ‘private organisations aiming to make some profit from their activities’) than those four types.

What else have we seen?

Ecosystem. The value web of organisations that produce products or services that together comprise a coherent solution. Collaborating in your supply chain. Creating a circular economy business model.

Industrial setting. The (global) sector and the geographical cluster(s) that an organisation is part of. An industry initiative to diffuse innovation like Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping. Creating a sector standard.

Political economy. How the economy functions, including the role and activities of the state. Lobbying (much of which is anti-sustainability). Industrial policy. Citizen assemblies.

These are unfamiliar, so need a bit of explaining. You can think of them as moving outwards.

‘Ecosystem’ is on level up from organisation. It is all the suppliers, sales and distribution channels, and customers that make the organisation successful. People will be more familiar with the terms ‘supply chain’ or ‘value chain’. But in our digitally-enabled world, things are less linear now and more disaggregated (or, in every day terms, ‘outsourced’).

The leading thinking is in terms of ‘value webs’. A company like Nike makes very little of what is sold in its name. There are suppliers (often in countries where labour is cheaper) and retailers. There is physical flow of items, from raw material to finished shoe or T-shirt. But the value creation is more complex, with a wider web of designers, sponsorships, sports, influencers and so on, all part of the Nike ecosystem. (And some will be part of other ecosystems too.) Nike acts as a ‘ring master’, focusing on the design, the marketing and coordinating the supply chains.

The industrial setting is the next level up again. There is a global apparel industry (which has its own Sustainable Apparel Coalition). Plus, there are regional clusters of apparel manufactures, notably in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka.

The level up from that we call ‘political economy’. We mean the conditions under which production or consumption is organised, within and between nation-states (to build on the Wikipedia description of the original meaning of political economy). So, how the economy functions, how the politics is playing out, and how those two interact.

For instance, when David started in Forum for the Future in the early 2000s, the idea of a government intervening to grow the sustainability-related parts of the economy (aka industrial strategy) was dismissed out of hand. The role of the state was much smaller. Markets would solve problems with little intervention from governments. Now, the US has had the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as part of EU, China, the UK and others trying to use industrial strategies for various policy goals, some of which are explicitly sustainability-related.

We could have called this scale ‘economy’ but that would miss something important. How the economy functions is not just the result of abstract, impersonal forces playing out. Some people and organisations have more power, and more resources, than others. They use what they have to tilt how the economy functions in directions they prefer (usually, but not always, for their own self-interest).

Politics always plays a part in how the economy functions, and how the economy functions plays a part in the economy. Hence, ‘political economy’.

Now, this overall innovation typology (product, process,…etc) has problems:

It risks making ‘innovation’ meaning any and all changes.

It is difficult to precisely categorise an innovation. One novelty could have effects at many levels. Plus the boundaries between levels are fuzzy.

Our claim is that articulating these types is useful because it reflects practice.

The sustainability leaders in business are trying out new products, new processes and new marketing methods. They are re-organising their company to better invent, innovate and diffuse those novel ideas-made-real. They are also re-shaping their ecosystem (aka ‘value web’ or ’supply chain’) while trying to change their industry. Some are also trying to change the political economy of countries, and even at a global scale, for sustainability-related outcomes.

Hence our foundational claim: every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level.

For completeness

I promised to not write everything in this series. And I promised to keep this entry short. At the same time, I can imagine the reader saying ‘but what about…?’. So, in this section I will give the section headings for the other things we talk about, but without going into detail

If you want detail , get in touch. We can use that as evidence that there is demand for a book!

Beneath the jargon, innovation and sustainability in business is highly political.

We will see pockets generating a better future and cynical attempts to defend a failing status quo.

Where we are in the ten lectures

Introduction -- here

0. Situating the module’s perspective:

0.1 The only viable story of the future is transformation. -- here

0.2 Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level. – this note

1.Business Responses to the Sustainability Crisis.

2.Innovation Economics: Core Concepts and Issues (with a transformative lens).

3.New Product Development and Managing Technology Innovation.

4.(a) Sustainable Entrepreneurship and the route to commercialisation.

4.(b) Sustainable Finance.

5.Innovation (eco)system – beyond the cult of the entrepreneur.

6.Sustainable innovation in a digital age.

7.Sustainability Strategy and Scenario Planning.

8.Transitions and The Bigger Picture.

9.Public Policy for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation.

10.Exploring Innovation and Sustainability through a Case Study.