Atelier WeekNotes for w/c 22 April 2024

PRIORITIES. Organising for Abundance: Lessons from PG Collective, & past strategy clients. 0/DETECTING. More SBTI. 'Moral debt on climate'. OUTPUTS. Innov 4 Sus: Molly Webb. ReadingNotes: PDIA toolkit

I am writing newsletter of #weeknotes of starting the Atelier of What’s Next (a studio for initiatives at the frontier of generating a better future). For my rationale for starting the Atelier see here.

Welcome to the WeekNotes for w/c 22 April 2024. This week covers:

PRIORITIES

Organising for Abundance

-Lessons from PG Collective.

-Lessons from past strategy clients.

0/DETECTING

-SBTI developments: finance for the Global South to keep the climate COP going?

-Economics Nobel Laureate: 'We have a moral debt on climate'.

OUTPUTS

-Innovation for Sustainability podcast: Molly Webb

-ReadingNotes: Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) toolkit

How can the Atelier of What's Next be of service to you, and your purposes? We'd love to hear from you. Perhaps you have a challenge or idea to put in the studio. Maybe one of our existing topics appeals to you. What if you love to make new things happen by being part of the studio? Or if you have feedback or comments that would improve this deck. Either click the button below or email davidbent@atelierwhatsnext.org.

PRIORITIES

Organising for abundance

Lessons from PG Collective.

One of the objectives for the year is to ‘integrate insights from similar organisations’. Recently Liam Black (serial social entrepreneur, more in this Powerful Times interview) connected me with Bob Thust of PG Collective.

PG Collective is a "a networked consultancy on a mission to help create a more equitable and sustainable society”, while Bob started in one of the big accounting firms (like me) and then made his way into advising for-impact organisations (again, like me). We had a lot of share heritage and perspectives. Key difference: Bob has been more of a self-starter, who has initiated more organisations.

PG Collective started as ‘Practice Governance’ and over its seven years there have been various phases, with ups and some downs as any new business should have.

My understanding of the operating model: 3 core partners; a number of associate partners; and a larger pool of associates and collaborator orgs. The core partners have prime responsibility, though all have expectations and contracts. PG Collective is able to assemble a team around a client’s challenge, with a strong preference of supporting the organisation as they do the work, rather than going off separately and coming back with The Answer On A 100 Slide Deck. (Very similar to what International Futures Forum (IFF) calls ‘practice advisers’.)

The lessons I took from Bob’s PG Collective experience:

People connect through real work. Build relationships (and test alignment) through doing things together. Bob’s preferred cycle was: win good work; attract good people; do good work as a way to get to know each other, and make sure it is worth keeping working together.

Build internal infrastructure as you need it (not anticipating what it should be and then find out you’re wrong). I could spend a lot of time on something which is not business critical, rather than on stuff which makes the most difference (attracting good work and good people).

Exact legal form not important. Pretty much any legal form can be made to work. You can layer what you need on top of a limited company (Ltd), or a limited liability partnership (LLPs) or a cooperative. So, don’t need to be too fussed on this to start with. Be wary though that some forms are much less flexible e.g. charities or community interest companies (CICs), though of course alot depends on what exactly you want to achieve.

Designing for agility. Employing people full-time is a big responsibility for an organisation, which then often feels obliged to win work that pays the wages, not which creates the change (a tension I was very familiar with when on the Senior Management Team of Forum for the Future). At the same time, many people are in the position where they can take on one project as part of a wider portfolio. So, it is now far easier to design for agility (including the changing volume of work) than before. This designed into PG Collective in the three levels (partner, associate partner and associate).

Embed values in practices. If the people are going to not have the security of full-time, and always have options about whether to be in a project team, then it is vital they feel well treated. Bob said PG Collective used ‘sociocracy’, a peer governance system based on consent (more here)

Giving space for a sense of ownership. Relatedly, with everyone involved, there is an iterative dance of testing their alignment to the organisation, and of revising the organisation in the light of that person. If good people are going to keep opting in, then they need to have a sense of ownership. As I’ve written before, that means I will need to be clear what of the Atelier is set, versus what can be revised when others join in.

All in all, an impressive organisation and an important set of lessons for the Atelier.

WHAT NEXT. Integrate these insights into the operational design of the Atelier.

Lessons from past strategy clients

This week I had a chance to get an update from two past strategy clients, organisations that I helped them form their way forward a few years ago. Bad news: both are struggling in important ways. So, a teachable moment, one of humility, for me.

I can't share the details, so you will have to trust my reflections:

It is not a 'good' strategy if it cannot be delivered. The temptation is to say that the strategies I helped them develop were good, they just botched the execution. Hurray, I'm off the hook! Only slightly defensive!

The deeper insight is that it cannot have been a good strategy if they could not execute it. The difficulties each organisation are experiencing were known risks when the strategies were approved.

Missing: good 'Design for delivery'. I'm still taken with Rummelt's kernels of a good strategy: a DIAGNOSIS of the critical aspects of the situation; a DIRECTION that outlines an overall approach for overcoming the obstacles highlighted by the diagnosis; and a DESIGN FOR DELIVERY, which is a set of coherent actions that are designed to deliver the direction.

I would say that events in one case have justified the diagnosis and the direction; for the other it is not yet clear. What was missing in each organisation was a design for delivery. Especially, in three ways:

Acknowledged the temperament and existing skills of the senior leadership and the organisational culture.

Built in agile learning steps to adjust the direction and design with experience (like the PDIA Toolkit below).

Keep telling your stories that reinforce your strategic choices.

Hard to keep alive your story of being a function in the system. In the impact world, people expect strategies to focus on topic-focused change approaches (‘we work on X topic by using Y method to get Z result on the topic’). You have coherence by having a consistent focus on particular content.

In both of my past clients, the core concept of the strategy was for the organisations to become core functions in the systems that they were already embedded. They were to play a role in a system that was otherwise missing. This is a process-focused approach. The coherence comes from consistently playing the same role on whatever topics are well-suited. So, you end up working on many topics.

If your test of strategic coherence is having a consistent focus on particular content, then working on many topics looks like lack of focus. But it is not, if your strategic choice is to play a consistent role in the system. (You can hear my frustration at having to explain this.)

All of which means, I think you need to keep telling the story of how you are playing a role in the system again, and again. And again. And again. Again. AND AGAIN. Until you're bored of it, until your vocal cords are bleeding with having to tell a slight variant yet again. And then people start to understand. (With the best will in the world, most people are atrocious listeners. Ye gads, atrocious. Anyway.)

I also think you need to tell this story at two levels: (1) the real, specific thing you've been doing, which illustrates (2) the abstract role you play in the system. Always lead with the real story, and then relate it to the abstract story.

All of which makes this experience very relevant to the Atelier, which is trying to be (in effect) part of the innovation function of the world. Keeping that story alive, and understood by funders and participants, is going to be a key challenge.

While it would be easy to read that last rant as me blaming others, I do just to reinforce: I should have pushed to do more on the 'design for delivery'.

WHAT NEXT. More focus on design for delivery:

Acknowledged the temperament and existing skills of the senior leadership and the organisational culture.

Built in agile learning steps to adjust the direction and design with experience (like the PDIA Toolkit below).

Keep telling your stories that reinforce your strategic choices. In the Atelier's case, the stories of contributing to the innovation function of the world.

0/DETECTING

SBTI developments: finance for the Global South to keep the climate COP going?

Two weeks ago I wrote about the SBTI controversy ('Who guards the guards?'). The board had announced an openness to carbon offsets, going outside of the procedure for setting its rules. Staff and technical advisers revolted; the board responded with a 'clarification'.

The fear is that allowing offsetting will open up at least 2 big problems. First, companies slowing down their own mitigation because they can just buy their way to lower emissions. Since offsetting will never be enough, slowing mitigation will slow the diffusion and learning effects of deploying technologies, which makes mitigation harder than it would otherwise have been.

That's bad enough without the second big problem: a lot of offsetting is rubbish, to put it mildly. In principle offsetting could be investing in new machinery which reduces emissions in a poorer country. In practice, a lot of offsetting is low quality with low confidence on quantity and additionality (whether it would have happened anyway). Think chancers planting lots of trees.

The question was: why did the board go outside the procedure? The speculation two weeks ago was that the Besos Earth Fund, a funder of SBTI and of the carbon offset market, had leant on SBTI. I wondered if billionaire funders are the friends of a socially-just, environmentally-secure future (as in, do we want to rely on these funders to fund public institutions like SBTI).

This week the FT carries a story (£) with a different explanation. Multiple sources said it was the US government's climate envoy, trying to unlock financing to go from rich-world countries to the Global South. Otherwise, the fear is that the UN climate negotiations (aka 'COP') will stall.

Nigel Topping, formerly High-Level Climate Champion when the UK hosted COP and now various roles (some deep in the carbon markets), told the FT:

"Those who held a “puritanical view” against carbon credits should come up with alternative ways to raise the trillions of dollars in financing needed to help the Global South adapt to climate change."

What if…we kept our promises? To which part of the answer is: rich-country governments could fulfil the promise they made in 2009, to mobilising USD 100 billion per year by 2020 for climate action in developing countries. The OECD tracker shows they (/we) have been well-short of that goal.

This work-around is…the best we've got? Really? It is easy to see why rich countries have failed to keep our promises, in the context of neoliberalism (governments should be small and not borrow), the financial crash (which slowed economies in 2009 and for years afterwards, especially where they went for austerity as response), rising nativist populism (look after our own first), and COVID.

Even so, below I highlight how Economics Nobel Laureate Esther Dulfo has other proposals.

The weird thing is that Nigel (who I know very slightly, and is definitely a well-intentioned, brilliant person with an unrivalled understanding of what is going on) sees a rule change in a relatively obscure private regulator of one esoteric marketplace as the main, if not the only, way to finance the response to climate change for over 80% of the world's population.

He may be right that this is the only bridge available to a better future. But that is extremely bad news that so much weight must be borne by such a very narrow bridge.

Frankly, if the on-going participation of the Global South in the climate COP process relies on this rule change, then how badly have we f*cked up in all the other aspects of climate finance?

WHAT NEXT. Follow developments, as they say, especially as this year's COP is supposed to be the finance COP.

Economics Nobel Laureate: 'We have a moral debt on climate'.

"I’m trying to put a number for the moral debt that rich people of the world — particularly people in rich countries — have towards the poor people of the world related to our consumption choices, and thereby our carbon emissions."

So begins an extraordinary interview with Esther Duflo, winner of 2019 Economics Nobel, in the FT (£).

The argument is, frankly, pretty obvious to those of us who have been in the field for a while: the poorest are most exposed to the impacts of climate; and "the majority of the damage is still done by us [in rich countries]". She calls this the moral debt of the rich part of the world to the poor part of the world.

She also proposes mechanisms to find the money: an 3% on the internationally agreed minimum floor of corporate tax (from 15 to 18%) and a 2% yearly tax on the wealth of the 3,000 richest billionaires. She has uses for the money (for instance, getting insurance for poor people who don’t have any right now).

She concludes that "It’s really necessary. And it’s reasonable. It’s not that hard."

My sense as I was reading it: yes, the rich parts of the world funding climate action in the poor parts of the world is necessary, but the idea of it actually happening all sounds rather impossible.

If this is “not that hard”, then I’d love to know what Dulfo thinks is hard. Freezing hell over? Going faster than the speed of light? Liking Piers Morgan?

I can't find the exact quote, but

gives a futurist maxim along the lines of: if it is unbelievable, then it is more likely a weak signal of the future.The unbelievable thing here is not the content of the argument (familiar for old timers like me) but who is saying it (a Noble Laureate in Economics) and where (the FT). Plus, it is unbelievable (to me) that it might actually happen.

Maybe I need to recalibrate what I think is plausible.

WHAT NEXT. Cross fingers.

OUTPUTS

Innovation for Sustainability podcast: Molly Webb

Next in the podcasts on Innovation for Sustainability conducted for the UCL Institute for Sustainable Resources, as a contribution to a module in this Masters. (You can find out more about these interviews, and the module, here.)

Molly Webb is Founder of Energy Unlocked, an energy market accelerator focused on new market entrants achieving a low cost, renewable, resilient energy system, and Co-Founder of PeerCo, a platform which boosts carbon impact for businesses through digital Monitoring, Reporting and Verification (Molly on LinkedIn).

We cover (amongst many things!):

-How the Energy Unlocked came out of Molly’s work at the Climate Group, and her diagnosis of the challenges for innovating in energy.

-How Energy Unlocked is a market accelerator, not a business accelerator. Molly is focussing on the conditions that would make it possible for multiple start-ups to succeed.

-One of the methods Energy Unlimited uses is Open Innovation.-Molly also uses a strategy approach called ‘Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation’ (PDIA).

-Relate the Energy Unlimited approach to the module’s innovation typology.

-If the incentives in the energy market were there, then we’d be fast on our way to a sustainable future already.-

There has been a shift to government-led industrial strategy.

-The Carbon Flex project, which asked asked the question ‘Are we investing in the right things at local level to decarbonise the grid faster?’.

-Part of accelerating a market is breaking new ground which is too risky for funding which wants a secure and certain return. Which makes it difficult!

-How understandings of the way energy markets work are very entrenched by how they happen to work now, rather than how they might work if you change the incentives.

-Addressing that inertia and entrenched situation requires exploring. Hence the need for Energy Unlocked.

-The importance of making sure the problem definition is not constrained by the understanding of what is currently possible.

-How important the demand side of the energy markets are, and how this is under-explored in policy, philanthropic funding and investment.

ReadingNotes: Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) toolkit

This post is part of the #ReadingNotes series, see here for more.

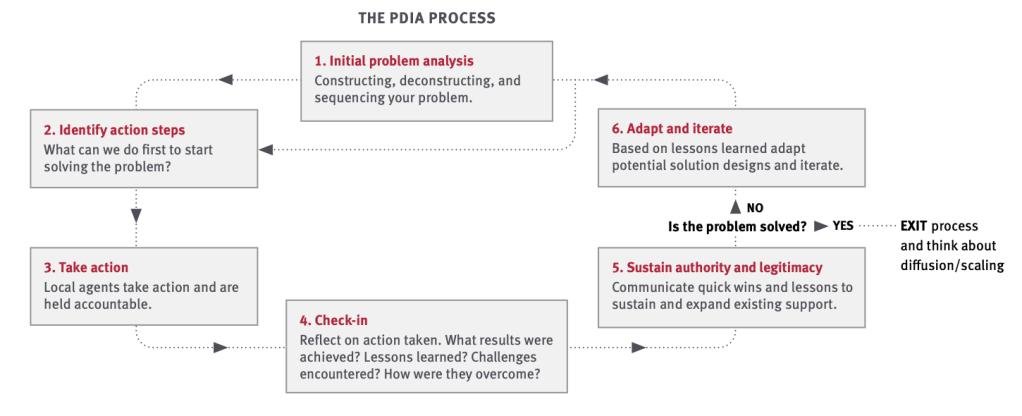

The Problem Driven Iterative Adaptation (PDIA) toolkit was developed by Building State Capability (BSC) at Harvard University, and "researches strategies and tactics to build the capability of organizations to implement policies and programs".

PDIA is a step-by-step approach which "helps you break down your problems into its root causes, identify entry points, search for possible solutions, take action, reflect upon what you have learned, adapt and then act again".

I would place it in a family of 'complexity literate' approaches, which put those insights into practice (others include: Cynefin Framework and Wasafiri's SystemCraft).

The PDIA approach rests on four principles:

- Local Solutions for Local Problems.

- Pushing Problem-Driven Positive Deviance.

- Try, Learn, Iterate, Adapt.

- Scale through Diffusion.

The PDIA process:

Constructing your problem. For the PDIA method a good problem: matters to people, can be broken into smaller causal elements, allows for sequenced responses that can be locally-driven.

Deconstruct the problem using Five Whys, and a fishbone or Ishikawa diagram to visually represent your deconstructed problem.

Find entry points by understanding the space for change, which is defined by 'AAA': the support needed (Authority); how much those affected by reform accept the need for change (Acceptance); and what can be done currently (Ability). You are looking for where there is large AAA as a place to start, with second priority to AAa (and the intervention is: what can be done to increase that small ‘a’ to a large ‘A’?).

Crawl through the design space for possible solutions. The space is Feasible here vs Technically correct somewhere. 'Crawl' as in: starting from where you are (A), avoid the siren of just doing what works elsewhere (D), increase capacity by trying better stuff that could be done now with some effort (B) and stuff that are already working but not the norm (C).

A. Existing Practice (Feasible but Technically not good enough). Scrutinise, learn from, and, maybe, improve.

D. External best practice (Technically works elsewhere but not feasible here). Identify, translate, adapt, diffuse.

B. Latent practice (Feasible but Technically mediocre). Provoke through rapid engagement, codify and diffuse.

C. Positive Deviance (Feasible and Technically correct, but rare). Find, celebrate, codify and diffuse.

Build and maintain authority for each iteration.

Design first iteration. Try a number of small interventions in rapid cycles. [Like a Sprint in the Agile methodology.]

Learn from your iterations. PDIA has no separation between the design and the implementation phase of solving complex problems. On-going iterating is part of the problem-solving. Targeted actions are rapidly tried, lessons are quickly gathered to inform what happened and why, and a next action step is designed and undertaken based on what was learned in prior steps.

I like the overall cycle and specific exercises within it (especially the diagrams above). I saw a family resemblance to the Boisot Social Learning Cycle (as used by IFF), on finding and scaling the Positive Deviance practices.

Least substantive objection: why is the process flow counter-clockwise?

More seriously, there doesn't seem to be a part of 5 or 6 about selecting which interventions to try (given limited resources). Also, the toolkit illustrates success coming after 6+ iterative cycles. So, I would have liked more attention on designing subsequent iterations, and keeping that going.

Finally, there is an implicit assumption that people can be creative, when prompted with all these questions. But maybe the context and culture provides too much of a constraint, or maybe, without practice, coming up with a new thing to do is a big ask.

Still, I can see applying this as part of the 'Act' stage in Imagining Influential Trajectories.

Citation: 'PDIA toolkit: A DIY Approach to Solving Complex Problems' Version 1.0 published in October 2018. Editors: Salimah Samji, Matt Andrews, Lant Pritchett and Michael Woolcock

Source: https://bsc.hks.harvard.edu/tools/ [23/04/2024]

Hi David: I think you’re referencing Dator’s Second Law of the Future here—“Any useful idea about the futures should appear to be ridiculous.” (Although he does also emphasis that this is not a syllogism—there are plenty of ridiculous ideas about the future that are not useful.)

More here: https://medium.com/@oriol_GG/https-medium-com-oriol-gg-why-you-need-to-learn-the-basic-principles-of-future-studies-806d7fead80e