Atelier WeekNotes w/c 11 Mar

Reflections on ‘Making a Market for the Metamodern: The Productive Tension of Corporate Futurism’

I am writing newsletter of #weeknotes of starting the Atelier of What’s Next (a studio for initiatives at the frontier of generating a better future). For my rationale for starting the Atelier see here.

My family emergency has moved from crisis to a more chronic stage. Hence, the late WeekNotes and only writing about one thing. But it is juicy!

This week covers:

0/DETECTING

‘Making a Market for the Metamodern: The Productive Tension of Corporate Futurism’

What I heard her say

'Futurism is making a market for meta-modernism'.

'The ickiness [she feels with corporate futurism] is the conflicted hope'.

Where I agree:

Corporate futures: often serving the status quo while pretending to bring difference.

Where I disagree

The 'ick': corporate futurism in particular, or any helping corporate?

Auditors show the limits of professional ethics.

Corporate futurism is not all futurism.

The future: a space to colonise/control vs as complex unfolding from now.

What can we do when the story of the future no longer makes sense?

Can we imagine a situation outside of our current or cumulative experience?

Is there a place to act Beyond Reform but before Make Good Ruins?

'To be alive is to meet new possibilities in creative ways'

How can the Atelier of What's Next be of service to you, and your purposes? We'd love to hear from you. Perhaps you have a challenge or idea to put in the studio. Maybe one of our existing topics appeals to you. What if you love to make new things happen by being part of the studio? Or if you have feedback or comments that would improve this deck. Either click the button below or email davidbent@atelierwhatsnext.org.

0/DETECTING

‘Making a Market for the Metamodern: The Productive Tension of Corporate Futurism’

Last Wed 13 Mar, I went to an event at Goldsmiths hosted by PERC, the Political Economy Research Centre. (As well as being just up the road from where I live, PERC is one of the partners in CUSP, the Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity led by Prof Tim Jackson.)

The talk was by Gemma Milne ( Gemma Milne ), a former journalist and more, based on her on-going PhD research at Glasgow University. The event blurb described her research as looking to "understand how corporate futurists make a market for themselves, how future-thinking is positioned as not only innovative and necessary, but – in some cases – righteous, and how corporate futurists navigate the perhaps contradictory nature of ‘making the world a better place for all’ within a corporate values-led environment".

She summarised her motivation as 'why does corporate futures make me feel a bit icky?'.

Given that I do describe myself as futurist, and have done corporate futures, it would be easy to be knee-jerk defensive. That said, I think I disagree with her conclusions, more because they are only part-right, but what I think is missing changes the overall shape of meaning (at least in what I think of as high-quality, good-faith corporate futures). But we'll get to that, after following Rapoport's rules on disagreeing.

What I heard her say

The talk had a lot of the theoretical building blocks that she was using to explore and explain, including Science and Technology Studies (STS), economic sociology, and critical management studies. She had conducted a number of interviews, but I don't remember her using (anonymised) quotes from them, or otherwise giving us a peak at that data.

Her conclusion: 'Futurism is making a market for meta-modernism'.

I have to confess I hadn't comes across meta-modernism, defined in Gemma's slides as "a structure of feeling characterised by oscillation between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony". (The wikipedia entry on meta-modernism has the original theorists grasping for a term to describe post-postmodernism.)

My question in the Q&A was: is the meta-modern that being sold either:

(a) the structure of feeling now (as in, the corporate executives get to feel the bouncing between modernity and post-modernity).

(b) the possibility of a meta-modern society (as in, the content describes a society which is post-postmodern).

She said all of the above.

But she concluded her talk that 'the ickiness is the conflicted hope'. The tone of all of her other answers in the Q&A was that corporate futurism pretends that something better is possible, but that is just a temptation, a distraction tactic that helps corporates have more power. Which is really only (a) with no mention (b).

As such, her conclusion was not really that there is a productive tension. More, a sense of disappointment, defeat, and even betrayal.

Where I agree:

Corporate futures: often serving the status quo while pretending to bring difference.

A lot of corporate futures work is, well, helping the powerful do what they want to do, slightly better. The report by a big management consultancy beginning with M____ or B___, paid for by industry X, which says -- surprise! -- that industry X will be large and important.

Another Jeremy Rifkin book and speech tour which says this one thing is happening, is unstoppable, and will mean this for the future.

There's also the Effective Altruists, who use the moral weight of a better future to prioritise success today, but amazingly always conclude that is success for the billionaires through tech and returns, not success for the billions through good public services and breaking up monopolies.

And so on. Corporates pay futurists to tell them how to succeed more. Futurists tell them. Either they help (in which case they are reinforcing the status quo) or they don't (in which case they are probably grifters). Either way, what can be imagined as a better world is often very narrow, today + more corporate success, while having lots of glimmers of something different as enticing distractions.

The possibility of making a difference squandered, or worse, sold away. No wonder it feels icky.

Where I disagree

The 'ick': corporate futurism in particular, or any helping corporate?

One of Gemma's themes was how much corporate futurists had to sell the method to corporates as a useful method to use. From experience, I know that's because corporate executives are, by nature, a risk-averse bunch. They will use the familiar tool, rather than a fitting one that is new to them.

One irony is that many of the familiar tools do have an embedded concept of the future, but just aren't explicit about it. For instance, a discounted cashflow (DCF) model gives an investment's revenues and costs for the years ahead. There are deep assumptions about how the context for the investment changes over time -- basically, nothing changes. (I have been told that M&S didn't refit their stores through the 2000s because their DCF assumed that the stores revenues stayed the same, even as the store interiors got older and older. The refit only made financial sense when they changed that assumption so that stores revenues declined with age. More on how financial tools are innovation killers because of unstated assumptions about the future here.)

The future will be today, except for there will be this project in it. Nobody calls that 'futures'. But that kind of planning is the default and dominant use of the future in corporate life.

in the nascent UCL futures practice group (admittedly, academic, not corporate) we have found that almost every method people are using to study sustainable energy or sustainable resources has some concept of the future in it.

I would have liked Gemma to have been sharper on her boundary that delineates 'corporate futures' from 'all corporate advisory'. And also be clear: is the ick she feels larger for the corporate futurists than for others? Say, the comms agency which comes up with a new marketing campaign, or the management consultancy which advises on a 'restructuring'.

Perhaps only futures carries the hope of something better (and 'it is the the hope that kills you').

But it is not only the futures field which is icky when it comes to working with corporates.

Auditors show the limits of professional ethics.

Gemma argued for greater professionalisation as a way get futurists to use their power better. The bad news is that auditors have a strong code of professional ethics, which is often enforced. Still there are big errors and scandals. (I was an auditor at PwC when scandal at Enron took down Arthur Anderson.)

Maybe there would be bigger errors and scandals in auditing without the code. But, my view is: as long as there are strong incentives, people will serve incumbent power.

Corporate futurism is not all futurism.

The end of the Q&A followed Gemma's conclusion headline in talking about futurism ('Futurism is making a market for meta-modernism'). But corporate futurism is not all futurism. At the end of the event, all were being tarred with the same brush, which isn't accurate or fair.

The future: a space to colonise/control vs as complex unfolding from now.

One of the key ways that the futures methods vary is on assumed nature of the future being engaged with. The very annoying book ‘Transforming the Future: Anticipation in the 21st Century’ (more on how it annoyed me here) gives this in two ways:

'Anticipation for Future' (AfF) treats the future as a goal – a planned/desired future that people bet on. This is the overwhelmingly prevalent form that the future takes when people use it in their everyday life. The future is a space to colonise and control.

'Anticipation for Emergence' (AfE) imagines a later-than-now as a disposable construct, a throwaway non-goal that need not be constrained by probability or desirability. The future is a complex unfolding from now.

Gemma didn't refer to the Futures Literacy stuff at all. I wonder if that would give her a different way of expressing the ironic nature of corporate futures.

Certainly, most corporate futures acts as if the future is a goal. But even within a project which is doing that, it is possible for some people to treat the goal as a disposable construct, that they use for other kinds of ends. (Those ends might still be icky, or emancipatory, or something else altogether.)

What can we do when the story of the future no longer makes sense?

In 'At Work in the Ruins', Dougald Hine quotes someone else (I don't have my copy to hand!) as writing: you know a culture is in trouble when the stories of the future no longer make sense.

He quotes the philosopher Federico Campagna, who also talks of living at the end of a world (taken from Just Two Things entry here).

"In such a time, he suggests, the work is no longer to concern ourselves with making sense according to the logic of the world that is ending, but to leave good ruins, clues and starting points for those who come after, that they may use in building a world that is – as Vanessa would say – ‘presently unimaginable’."

As I argue in the UCL Module lecture here, the current story of continuing growth makes no sense, it leads to collapse.

In this context, could Gemma's sense of metamodern ("a structure of feeling characterised by oscillation between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony") be a feature of corporate futures? Or, might it be a feature of this current time and place (which she then sees in corporate futures)?

Can we imagine a situation outside of our current or cumulative experience?

Also in that lecture, I argue that 'The only viable story of the future is transformation', one which is as deep as the industrial revolution. The changes played out at more than an economic level. How people lived, where they lived, how they interacted with each other, who had power, how politics was organised -- all of these changed over a period of decades.

But that puts us in a great problem. How can we imagine a situation which is so outside our current or past experiences? How can we make 'good' choices about what to do?

As L.A.Paul argues, a transformative experience puts us "a special sort of epistemic situation. In this sort of situation, you know very little about your possible future...You find yourself facing a decision where you lack the information you need to make the decision the way you naturally want to make it — by assessing what the different possibilities would be like and choosing between them."

This is especially true what you (and society at large) value are likely to change through the transformation. Medieval scholars could not imagine our world, and would see it as as a unholy hell with no reassuring hierarchy. We look at their time and cannot understand their commitment to a Great Chain of Being. Neither of us would want to swap places.

(incidentally, this is one reason why Richard Sandford's exploring of virtue ethics is interesting. He places the emphasis on ethical judgements in the present, but without requiring the present's dominant morality to be right. Perhaps this is also why Gemma touch on using pragmatism, as it is a rare ethical approach which doesn't require purity or perfection.)

If we can't imagine a future after transformation, then if the disappointment in metamodern is because it is still tied to the failing present? (The clue that it is tied to the present in the name.)

Is there a place to act Beyond Reform but before Make Good Ruins?

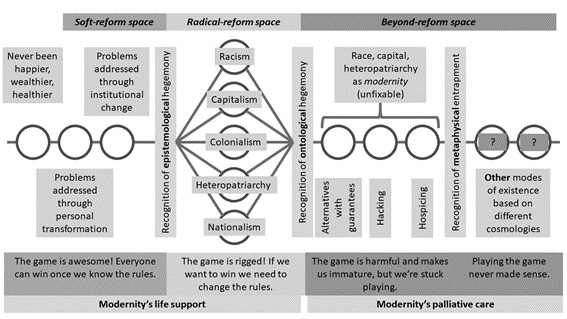

In Hospicing Modernity, Vanessa Andreotti (writing as Vanessa Machado de Oliviera) argues that there are three orientations to modernity:

Soft reform. With the right changes to existing institutions reform (and personal changes) modernity will benefit everyone.

Radical reform. With transformation of institutions then we can remake modernity into a just and fair version.

Beyond reform. Modernity requires social injustice and deep environmental harm. Soft and radical reform can reduce that harm. But the big picture is a need to hospice modernity.

This struck a chord with me. But I have found there are more variations within these three categories. So, I added to it to create a (doubtlessly flawed) 'depth of change spectrum' (past WeekNotes here, then here and here):

The hardest of these categories to imagine is Deep Transformation. We are living in times when people enact soft and strong reforms, and I'd argue that is where most Corporate Futures operates.

There are some people pursue radical resistance. For instance, listen to Prof Julia Steinberger on her degrowth work here.

We have stories of bad ruins, whether from the real experience of colonialism (Amitav Ghosh's The Nutmeg's Curse, The Rest is History on Fall of the Aztecs) or any number of science fiction novels and films. Good ruins are harder to come by.

My point is: what would attempts to imagine and enact Deep Transformation will look like to those rooted in the present? Would they come across as 'oscillation between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony'?

Do those attempts get labelled as 'metamodern' not because they are trapped by modernity, but because our way of understanding those attempts is trapped by the status quo?

Do we have a viable way of labelling glimpses of a transformed future? If there are ways to act Beyond Reform but before Make Good Ruins, how would we recognise them?

'To be alive is to meet new possibilities in creative ways'

Drawing all those thoughts together:

Yes, corporate futurism is often used in service of incumbent power. (It is appropriate to feel icky about >90% of that work.)

Corporate futures is not the only discipline that does so, and arguable others are more important. (It is appropriate to feel icky about >90% of work with corporates.)

Incumbent power is part of a failing status quo, where we are struggling to have viable stories about the future.

In that context, it will be easy to see any attempt to tell a story about the future as disappointing, because it does at least one of:

Reinforcing today's dynamics, or

Describing ruins (and so our failure), or

Imagining a world so different from our own that it seems ridiculous.

We don't have ways of thinking or categories which are from a transformed future.

There is a possibility of glimpses of a transformed future, particularly ones which centre on creating a world beyond racism, colonialism, heteropatriarchy, nationalism, growth and capitalism (rather than ones which centre on opposing a core feature of the status quo, and therefore unintentionally perpetuating those as core features) . In my terms, integrating the insights of radical resistance, but not 'just' making good ruins.

Because this does not have a recognised category yet, the pre-existing frame of 'metamodern' risks flattening out any futures efforts into things tied to the status quo (whether as modernity, postmodernity or post-postmodernity).

I left the event disappointed. It left me with a sense that nothing can be done. Even futurists just reinforce the present! Nothing can be done!

Maybe that is a result of Corporate Futurism (Gemma is right on conflicted hope). Maybe as a result of Gemma's research method (which, I fear, risks flattening Corporate Futures work because recognising a transformed future is so hard). Maybe because the UK is exhausted from a decade of terrible government, and I/we struggle to imagine better.

The antidote to that disappointment is in Bill Sharpe's Three Horizons: The Patterning of Hope (my review here).

Three Horizons is a futures method, and one quite widely used in corporates. You can use the method in quite a flat way. But, for Bill, the importance is to use the method with what he calls 'future consciousness' -- an awareness of the future potential of the present moment.

“We inhabit a universe that is always revealing new possibilities that have not been lived before…and to be alive is to meet those possibilities in creative ways, renewing the familiar in our own way, and making our own part of the new together with others.”

Bill argues for us to act with "a belief that, whatever the current circumstance, there is a way to act that expresses the possibility of a renewal of the human.”

All of Gemma's findings can be true. But still miss the small moments of people practicing their future consciousness, their awareness of future potential in the present, even in a corporate context. And it is in those small moments that a future after the status quo will be made.

Thank you to Gemma, for prompting my thinking!