EVENT REPORT: Good faith arguments against 'post-growth'

Ecosystem thinking for a post-growth future. Good faith arguments against: their responses, and my list. New framings needed.

I am writing newsletter of #weeknotes of starting the Atelier of What’s Next (a studio for initiatives at the frontier of generating a better future). For my rationale for starting the Atelier see here.

Two weeks ago I went to a postgrowth event which got me pretty riled up. I had wanted to put my thoughts in the WeekNotes w/c 21 and 28 April 2025. But the section was just getting bigger and bigger, and delaying sending out the WeekNote.

Instead, my thoughts on the event are here, in the following sections:

Introduction.

Ecosystem thinking for a post-growth future

Good faith arguments against: their responses.

Good faith arguments against: my list.

If all ecosystems reach dynamic stability, how come the curve of biodiversity keeps going up over the last 4.5 billion years?

If resource limits induce innovation through increased prices, is that really a fixed, immovable limit?

Can regulation that imposed by rules (that are not hard-wired into inner dynamic of a system) really be as inevitable and reliable as self-regulation (which is hard-wired into inner dynamics)?

If the transition requires mass social engineering (including suppressing masculine-coded values of power and achievement), how is it ethical or practical?

How would any postgrowth economic activities out-compete currently existing economic systems?

How is it scientific, or wise, to bet our entire existence on one, current interpretation of how ecosystems work?

How can we guard against using science to do what we want anyway?

Are the limits truly about nature, or about us, and how fast we can adapt to changing circumstances?

Conclusion: new framings needed.

I hope to put out a WeekNote for w/c 5 May tomorrow. Enjoy! -- David

Introduction

On Thu 1 May I went to an academic seminar and book launch Debating Post-Growth Futures, hosted by The Bartlett, UCL's faculty of built environment. (The Bartlett is much wider than you'd imagine from that title. For instance, it includes Prof Mazzucato's Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. >shrug<)

Regular readers will know that much of the post-growth / de-growth debate gets my goat. It is very polarised, with lots of shouting and not-listening from both sides. My hypothesis is that both sides have made their positions part of their identity, and so have stopped examining for good faith arguments against their position. Because to question their position is to question in a real sense who they are, and to risk sanction from their in-group to which they feel a sense of belonging.

As I have written previously, I think that both the pro-growthers and post-growthers are a bit right and also very wrong.

There is a lot on what I think the post-growthers get wrong below. So, it is probably useful here to be clear that I am not pro-growth, otherwise people might dismiss the below as the same old shutting eyes to realities.

Where I agree with the post-growth position: more growth of today's economy = bad. Growth of the global economic system in its current configuration will take us through thresholds in nature which will, first, decline in performance, and, eventually, collapse. Both decline and collapse in nature would cause huge suffering, and likely lead to something we would call a global societal collapse by the end of the century. We need to consider the economy, and all of humankind, as a part of nature, that we affect and also rely upon. We need nature to be able to cope (better: thrive) with humankind, and us to cope (better: thrive) with nature.

Where I disagree with the post-growth position: the only possible way forward is to pursue post-growth. I think that rules out other directions we might pursue. And, as you will read below, I think some of the foundational assumptions of post-growth are at best contentious, and worse, flawed.

If you read the below and think "he's just an apologist for the status quo!" go read the opening lecture of the 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business' module I co-lead, which is titled: The only viable story of the future is transformation.

Enough throat-clearing. Now, I will follow Rapoport / Dennett's requirement for successful critical commentary, expressing the key note speakers views in a clear, vivid and fair way, before moving to my critique.

Ecosystem thinking for a post-growth future

The key note was from Simonetta Tunesi, a leading commentator from Italy. She has just publish a book in Italian, IL FUTURO STA NEI LIMITI: Gli Ecosistemi ci insegnano come fare (Google translates this as: "THE FUTURE IS IN THE LIMITS: Ecosystems teach us how to do it").

My summary of her argument (taken from my notes of her talk and the Q&A immediately afterwards):

The existential crises we faces are disruptions of balances caused by dominant socio-economic system's refusal to acknowledge the three limits of nature:

Limited resources: land included.

Limited capability to neutralise pollution.

The slow pace at which nature changes.

Geopolitically, there have been two strategic responses.

Western growth-believers recognised the limit in the capacity to neutralise pollution, and so have gone for a strategy of decarbonisation. This ignores the limited inputs.

China recognised the limited resources, and so pursued the well-known route of predation and huge industrial complexes. In many ways a return to East India Strategy: the state can't invade directly, so charter private entities to own land in a different nation.

Both strategies continue to challenge the Earth systems non-negotiable limits.

The post-growth question: Will the 'fight for finite' control us and determine a collective evil-fare, or will reformed systems control hubris and ensure shared welfare?

The goal of a post-growth perspective to redistribute the benefits of resource extraction and transformation with equity while respecting Earth System balances. (Contrast with Trump, who is fine with his tariff policies reducing consumption (US kids might have 'two dolls instead of 30'). His approach is chaotic and will fall heaviest on the weakest.)

The only way forward is to organise our societies in ways that align with how natural systems organise and endure, including:

After a period of growth, ecosystems always reach a stable dynamic equilibrium. At this point the inner dynamics of the ecosystem enforce dynamic stability. In the simplest example: rabbits multiple, there is a delayed rise in foxes as they have more rabbits to eat, rabbit populate declines, foxes also, repeat.

There are finite resources that can act as inputs. For instance, there will not be enough critical metals for everyone to have a green growth transition.

The four principles to organise around (with example policies):

Adapt production and consumption to the Earth's natural finite resources. For example: Set annual per capita limit and curb luxury consumption by rich.

Distribute resources within complex social networks recognising the role and relevance of each social actor, national and international. Have strongly progressive taxes and reduce military spending.

Encourage a network of distributed units of energy and food production. Energy communities and 15 minute cities.

Reuse matter in circular economy. Everything made either last, reuse or recycled.

Take the time to assess the consequences of socio-economic choices.

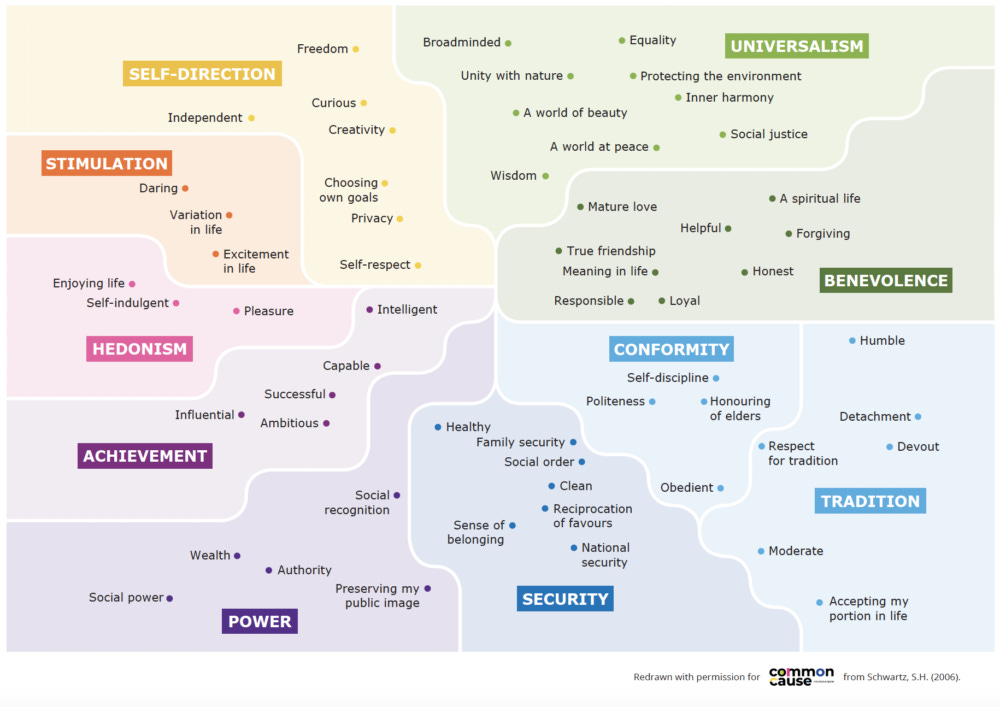

In order to deliver a transition, we will need to change the values that majority have. In terms of the Common Cause Values Map, reducing the dominance of Power and Achievement, and making Universalism and Benevolence dominance instead.

Good faith arguments against: their responses.

After her keynote, Tunesi was joined by a panel (Daniel Durrant, Lecturer in Infrastructure Planning at The Bartlett; Tommaso Gabrieli, Associate Professor in Real Estate at the Bartlett; Lucia Cerrada Morato, Research Fellow at Institut Metropoli), all of whom were arguing for a post-growth future, though with different emphases.

I like to ask an open-ended question on the weaknesses of an argument at events. That’s not because I can’t guess at what those weaknesses might be. Instead, I’m seeing if the speaker has been curious and rigourous. If they can answer well about the limitations of their position, my judgement is that the case for using their findings is stronger, precisely because they know the limitations. (More here.)

On this occasion, I asked 'what are the good faith arguments against this position, and how do you answer them?'.

The panel plus Tunesi gave the following:

Pursuing post-growth would have a de-stablising effect which is unpredictable. National finances rely on growth, to pay off debts. The bond markets might punish a country that tried. (Just as they have punished Truss and Trump for steering too far from the orthodoxy, though in T and T's case they were going for economic growth by reducing the state.) Historically, the reaction of the bond market has been overcome, for instance with collective debt forgiveness programmes. (I agree, and think it is useful to think of global finance as neoliberalism's enforcer.)

Growth is theoretically possible indefinitely, just different kinds of things. For instance, a service-orientated economy which valued experiences over things. (In 2007, I was part of a project imagining such a scenario, which we (Forum for the Future plus HP Labs) called Redefining Progress, in Climate Futures 2030.) But, even in such a society, there are still resource costs and energy use of virtuality.

We do need to build new homes, grid infrastructure for renewables, and so on. The counter: when you ask housing experts in the UK, they admit we don't need to build new homes, just occupy the ones that already exist.

Only growth delivers more economic resources, which then makes everyone better off (eventually). While a common argument, the panel called this the trickle-down effect, which had been demonstrated to not exist. (Though, I'd note the argument for the trickledown effect is more about the time since 1980. I'd wager that the poorest in the UK have better quality of life now compared to pre-capitalist growth, say in 1600. As Michael Jacobs said in a lecture I attended, who extremely few people would be willing to live all their life in pre-capitalist times (especially given the infant mortality).)

Losers from sudden austerity will be the weakest and poorest. This is a very valid concern, but can be overcome through coordination. Also, shows how important having progressive taxation is, as this provides the resources to invest in transition infrastructure.

All of these are strong arguments, and many fall under the umbrella of 'we are currently reliant on growth, so any change will be painful, especially for the weakest -- and therefore we need to plan and coordinate carefully'. But are these the strongest good faith arguments against the proposition?

Good faith arguments against: my list.

A slightly leading question, to which my answer is 'f*ck no!'. There are some good faith arguments against the fundamentals of whether it is necessary or wise to pursue post-growth. (In my WeekNote last year on the Deep Transition Lab event in September, I wrote a long-ish piece on why I think focussing on degrowth or postgrowth is a serious mistake. Go to that more depth on some of the points below.)

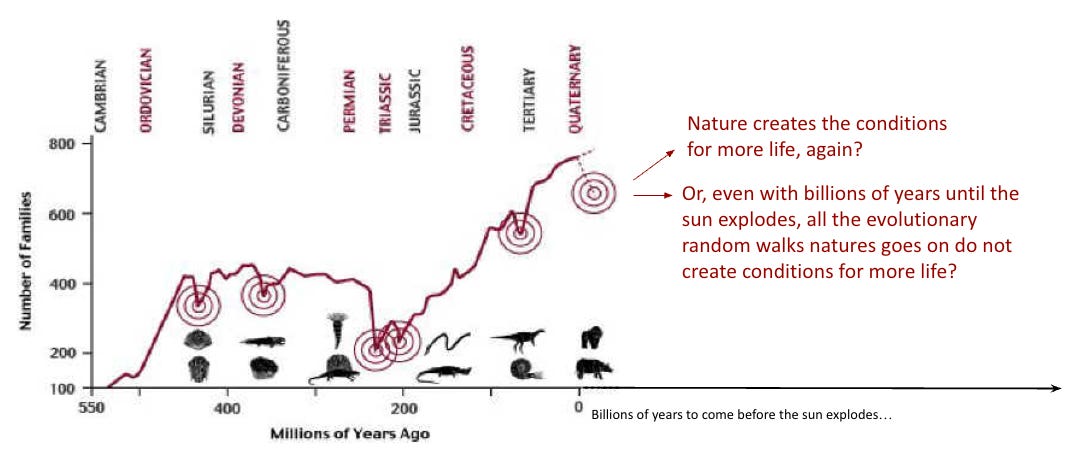

If all ecosystems reach dynamic stability, how come the curve of biodiversity keeps going up over the last 4.5 billion years?

From Sep: "We have billions of years of evidence that the energy input allows nature to keep on converting 'dead' matter into living organisms, and also keep going with the random walks of evolution, generating new species and ecosystems over time."

Yes, the Earth is a walled garden. The resources inside the garden are fixed. But the sunlight provides nigh-on infinite energy, if delivered on a geological timescale. Some 4.5 billions ago there was no life. Now there is lots. In 9 billion year's time, will nature have found an upper limit to the amount of life on the planet?

What is the evidence that nature at the global scaled (rather than local ecosystems) necessarily and always reaches a dynamic equilibrium?

If resource limits induce innovation through increased prices, is that really a fixed, immovable limit?

Two of the physical limits Tunesi talks about have different relationships to economies. Whoever creates downstream pollution does not have to pay for that. Only when regulation comes in do they have to incur a cost, whether buying a permit, paying a fine or changing their production process. (This is why, in my understanding of the Limits to Growth scenarios, it is pollution that causes collapse. The natural world can no longer cope, and ecosystem collapse leads to civilisation collapse.)

But, whoever is taking resources does have to pay to get them, at least for the effort to extract them. (Though not for all externalities, like using up an option that future generations might want, or destroying biodiversity.) So, if a resource becomes harder to extract the price goes up. If the prices goes up, that induces innovation, either to use less of the input per unit of output, or in finding a substitute, or to looking hard for more deposits.

The prices of commodities have usually gone down, even as we have used more and more. Famously, economist Julian Simon bet against Paul 'Population Bomb' Ehrlich on resource scarcity, saying that market forces would keep commodity prices from rising, even with higher consumption, in the decade to 1990. Simon won the bet (and would have done so in more-or-less in every decade since the 1930s).

Yes, there is finite material in deposits. But, in principle, couldn't a circular economy (powered by renewable energy) use the existing circulation plus past trash to provide enough materials, as long as there is ongoing innovation of use per unit and substitutes, and also accompanied by a shift from valuing ownership to valuing access and experiences?

Given the history of failed predictions of when we will run out of material X, how fixed and immovable is this limit, really?

Can regulation that imposed by rules really be as inevitable and reliable as self-regulation?

The longer version of this question is: "Can regulation that imposed by rules (that are not hard-wired into inner dynamic of a system) really be as inevitable and reliable as self-regulation (which is hard-wired into inner dynamics)?"

In Tunesi's simplified example, the rabbits and foxes keep each others’ populations in a dynamic equilibrium. The 'regulation' that holds the dynamic equilibrium in place is hard-wired into the structure of the system. It is self-regulation.

There is not an external institution that sets an upper limit for rabbit population, and releases more foxes when an indicator is triggered. Or who can be bribed, or removed by some kind of rabbit putsch, so that upper limit is set ridiculously high, or that only a token number of foxes are released.

In short, the ‘self-regulation’ of an ecosystem is not from 'regulation' as we commonly mean it — a state or other body of authority penalising those who are going too far. Nor are their bad actors who can shift the dynamics in their favour.

There is a huge risk that policies and regulations would be observed -- up until the critical moment, when the most powerful or most rogue would decide the rules no longer worked for them

Arguably, that is what is happening now with the USA. Since the end of World War 2, and especially since the collapse of communism, the US has used its hegemonic power to support a set of global institutions, like the World Trade Organisation, that, very imperfectly, pursue a liberal, free-market, rules-based order. Countries could sue the US, and win (eg here).

The threat of the imposition of the rules meant most large players, most of the time, played by them. (There are many exceptions. But the fundamental point stands.)

But, when globalisation got tough, the tough stopped supporting globalisation. First slowly, for instance making it very difficult to appoint judges in WTO, so there were much less threat of penalties, or having an active industrial strategy. Then suddenly, Trump taking a chainsaw to the global trade architecture.

Self-regulation that doesn’t withstand such pressures is not self-regulation that will take us to, and keep us in, a post-growth world.

That's even before considering what rogue nations would do. More of this argument here. Basically, this is why I think that the only viable story about the future is a transformation of the economic system, because then there is the possibility of aligning with nature can be hard-wired into the the inner dynamic of the system, and be self-regulating. (I'm not saying that would be easy to do.)

What evidence is there that we can create an enduring local and global governance which will not be stable or enduring?

If the transition requires mass social engineering (including suppressing masculine-coded values of power and achievement), how is it ethical or practical?

It was in the Q&A after her talk that Tunesi said we will need to change the values that majority have, and used the Common Cause Values Map above to say we will need to reduce the dominance of Power and Achievement, and making Universalism and Benevolence dominance instead.

This statement, and the rather blithe attitude embedded in it, really, really annoyed me on the day, and still does.

On an ethical level, who are we to determine what values people are allowed to have? Isn't diversity something that people in sustainability usually advocate? What about needing a requisite variety of values? Or is it diversity for the metropolitan, educated, globalist anywheres, but exclusion for the small town, less educated, nationalist somewheres?

How does mass social engineering fit with notions of democracy or liberalism? Are we to jettison those too? (And if you are advocating an authoritarian government, how does that make you different from Trump or other Big Man populist? Also, how will you make sure all future leaders are as benevolent a dictator as you want now?)

Do you realise how many of Umberto Eco's 14 general properties of fascism you are ticking? How many properties of fascism is it OK to tick before it gets to be a problem? How is your proposal different from ecofascism?

As it happens I am reading Gods in Everyman by Jungian psychotherapist Jean Shinoda Bolen. In it, she starts with a powerful and compelling argument that patriarchy is bad for both women and men. So, I agree that that the current values of our culture are good, or that it would be useful to find some way to boost particular pro-sustainability values (often female-coded) and deflate the anti-sustainability ones (often male-coded).

Being a Jungian, Bolen understands patriarchy as an expression of the Zeus archetype -- the sky-father who pursues power over others and is obsessed with achievement. She describes how deeply embedded that archetype is in our cultures and in our psychology.

But, now, all we need to do is replace the Sky-Father as the main archetype activated in our Western / global collective unconscious for over 2,000 years, and then everything will be fine!

Sounds easy! Or...

Or maybe not. Maybe it would be extraodinarily hard

Also, maybe worth paying attention to the toxic hyper-masculine that characterises most of the nationalist populist movements around the world. One way to understand these is as a counter-revolution to a perception that the West has become weak because there has been a rise in women and of female-coded values (more here). Woke is universalism and benevolence. Anti-woke is this quote from the FT: “I feel liberated,” said a top banker. “We can say ‘retard’ and ‘pussy’ without the fear of getting cancelled . . . it’s a new dawn.”

So, maybe trying to push down male-coded values and grow female-coded ones might give rise to such an almighty backlash that you fail spectacularly? Worth considering, I think.

A friend of mine who is a political operative from the centre-right has often told me he wishes more people on the Left read The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt. When I read it, I was forced to realise that values I dismissed, like sanctity or authority, are important to people, and also respecting those values (and those people) is important to a well-functioning society.

Take John Lennon's Imagine. I'd guess most readers of this newsletter think the lyrics are uplifting ("imagine there's no countries"). But Haidt argues here that for many people, these sentiments make them sick to their stomach. At the core of their identity is belonging to a national community, which is closely bound with other ways of being normal.

For societies to function, all of us have to be willing to restrain ourselves and live according to rules and norms. Now reconsider the lyrics: no countries, no possessions, no heaven or hell; the world being as one. Can all individuals thrive when there are no boundaries, and you are one in 8 billion?

As Branko Milanovic writes in his review of Raworth's Doughnot Economics:

"In many instances, Kate writes in the first-person plural, as if the entire world had the same “objective”: so “we” have to make sure the economy does not exceed the natural bounds of the Earth’s “carrying capacity”, “we” have to keep inequality within the acceptable limits, “we” have an interest in a stable climate, “we” need the commons sector. But in most of the real world economics and politics, there is no “we” that includes 7.3 billion people."

Different classes and different geographies have different interests. No amount of imagining will make that go away.

Be very careful of the global ‘we’.

Just on a sheer pragmatism, the incumbents who will defend the status quo have far more resources and own or control media and many of the channels of communication across society. Even if it was ethical and a good idea, how will the pro-sustainability movement manage to do mass social engineering at the pace required to stay under 2C, given that the incumbents will use their resources and access to fight back?

As I say, all the objections above do not mean that we should just leave societal values alone. But we need to think carefully about how to contribute to how the on-going shaping and activation of the strongest values in society. For instance, it is possible to harness Power and Achievement values for the benefit of ecosystems and people?

In short, FFS. If you are going to advocate for shifting societal values, think it through critically, and stand in the shoes of others.

What is the evidence that the transition requires this mass social engineering, and that it can be pursued in practice on the necessary timescales with the resources to hand?

How would any postgrowth economic activities out-compete currently existing economic systems?

Historically, growth-orientated capitalisms have been able to, well, grow. To a first approximation, non-capitalist societies either reorientate to being part of the capitalist world-system, or get colonised. See the recent Past Present Future episode on the fall of the Berlin Wall for a discussion of how most then-communist countries ended up capitalist (Easter European countries via shock therapy; China and Vietnam through internal reform).

Any large-scale alternative will need an inner dynamic, a flywheel, which delivers for citizens, draws in the resources that it needs, creates the knowhow it needs, and resists the responses of the capitalist world system.

How would a postgrowth economy create a flywheel dynamic which meant that it would replace the status quo?

How is it scientific, or wise, to bet our entire existence on one, current interpretation of how ecosystems work?

I have worked in sustainability for over 20 years, and just before that I did a Masters in Responsibility and Business Practice (now defunct but here is the archived web page). I have heard from many people, and read many papers and books, that we need to align human society with the laws of nature. I agree.

The trouble is that they each have different laws of nature, sometimes small differences, sometimes big.

Tunesi had four principles. I don't disagree with any of them. And also, I've been told with great confidence different principles of ecosystems by other people.

Yes, we need to use the latest science to craft our way forward. But we need to do that knowing that (1) there can be several competing scientific understandings of something legitimately existing at the same time; and (2) the latest science will change over time.

Building a society around one scientific understanding means that any errors in it will be astonishingly important. (The Soviet Union under Stalin supported Lysenkoism, a theory of biology which aligned with Marxism but rejected natural selection. It's errors prolonged famines, and led to millions of deaths.)

As such, betting the farm on one particular way of describing ecosystems is the opposite of scientific, because it gives no space for the scientific method to generate different ways of describing ecosystems in the future.

How can we use the latest science while still respecting the scientific process?

How can we guard against using science to do what we want anyway?

"UCL acknowledges with deep regret that it played a fundamental role in the development, propagation and legitimisation of eugenics. This dangerous ideology cemented the spurious idea that varieties of human life could be assigned different value. It provided justification for some of the most appalling crimes in human history: genocide, forced euthanasia, colonialism and other forms of mass murder and oppression based on racial and ableist hierarchy."

That is the first paragraph of UCL's apology for its history and legacy of eugenics.

There was a time when the field of eugenics was considered scientific, and was used to as a scientific basis for the values people had.

Everyone advocating using ecosystem science for re-orientating society is doing so because they believe it will be best for people and the world. I'm not accusing anyone of wanting to commit appalling crimes. Indeed, the intent is to avoid huge suffering from ecosystem collapse.

Instead, the example of eugenics is a warning from history about using science to justify what you want to do anyway.

Many of the policy proposals in Tunesi's presentation have long histories in the progressive politics, from before ecosystem science was well-described. I imagine most of the people in the room would have agreed to them if they had been proposed in 1950 or 1970, with whatever rationale was used at the time.

My worry is that Tunesi and the panel seemingly had no critical awareness of any of this. They were very convinced all their rationale was accurate and well-intentioned.

What are the governance processes in the postgrowth movement, and in what it proposes, to safeguard against technocrats using science to justify their pre-existing preferences?

Are the limits truly about nature, or about how fast humankind can adapt to changing circumstances?

My view is that, on geological timescales, nature will keep on creating the conditions for its own success. Life finds a way.

Let's imagine that there is a transformed global human system, and all our societies, which does not undermine the natural basis on which humankind relies. There is a set up where we can cope with nature and nature with us; an on-going co-evolution.

Why would there be a limit on the financial value of such human activity?

The limit would be our alignment with nature, not nature's current limits.

Of course, it might turn out to be impossible to for us to go from where we are today into large and complex societies that can co-evolve with nature.

But the limitation there is humankind's capacity to change and align with nature, not planetary boundaries.

And by 'change' here, I do mean reduce the harms being done to ecosystems (so mitigating GHG emissions, for instance), not just giving up and adapting to the inevitable.

How can we increase humankind's capacity to change, so that there are viable paths to future states for humankind and its societies that are an enduring and safe global society, where people can choose their version of the good life, and humankind is co-evolving with nature?

Conclusion: new framings needed

It has taken me over a week to write all of this up. But, I had versions of all of my good-faith challenges in my notebook during the event. It should have been possible for the panel to go deeper than their list.

That is one reason for going into depth. I'm not a full-time academic! I shouldn’t be able to think up stuff which they haven’t!

The event was billed as a debate, but all all four speakers agreed on the fundamentals. I realise that the post-growth movement has been having to protect itself from attacks by those who support the status quo. (Back in 2016, I had conversations with academic economists who had missed promotions or been moved on because they didn't have enough publications in quality journals. Those quality journals just rejected degrowth papers by default.)

But, my view is that now is the time to say: "we've protected our niche to a point where we have more people and credibility. Now is the time to open up to good-faith challenges, in order for our work to go deeper and be more impactful."

Also, framing what needs to happen as ‘postgrowth’ ironically keeps the centrality of growth in the frame. The label, and the substance that follows, is still trapped in terms of the status quo.

Instead, can we frame whole change and research agenda in terms of the transformation to humankind being aligned with nature?

What are viable paths to future states for humankind and its societies that are an enduring and safe global society, where people can choose their version of the good life, and humankind is co-evolving with nature?

What might that mean for how our economies are organised so that those qualities were features of their inner dynamic and structure?

What role does the rate of change of the size of the economy play in the different pathways and economic models?

What are the ways of starting in roughly the fight direction, and learning along the way?

And so on.

I think there is a more generative research field (and change effort) to be had, by stepping out of the growth (and its variants) framing.