1. Business responses to sustainability crises

The recent history of ‘sustainable business’. Relating to the academic literature. Highlight: Stakeholder Capitalism.

This short SubStack series gives a weekly key insight from the Masters module I co-teach on 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business'. All those posts are gathered on this page. The Atelier of What's Next WeekNotes continue in parallel.

This week:

Overview of this lecture/chapter.

The recent history of ‘sustainable business’.

Relating to the academic literature.

Highlight: Stakeholder Capitalism.

What are we contrasting with?

Background of stakeholder capitalism.

The difference with shareholder capitalism.

Some challenges of putting stakeholder capitalism into practice.

Stories from the UK context.

Cooperatives as a version of stakeholder capitalism.

Now in use with for-purpose business approaches.

Where we are in the ten lectures.

Overview of this lecture/chapter.

Up to this point we have been laying the foundations of the module, especially the overall purpose of the module, and foundational assumptions on: the need for transformation; and, how every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level.

This lecture looks at:

The recent history of ‘sustainable business’.

This uses David’s experiences as a series of stories about what happened in sustainable business from 2003 to present. Many of these are from his time at sustainability NGO Forum for the Future, where David was Director of Sustainable Business. He led the advisory service that helped big businesses combine being successful with creating a sustainable future.

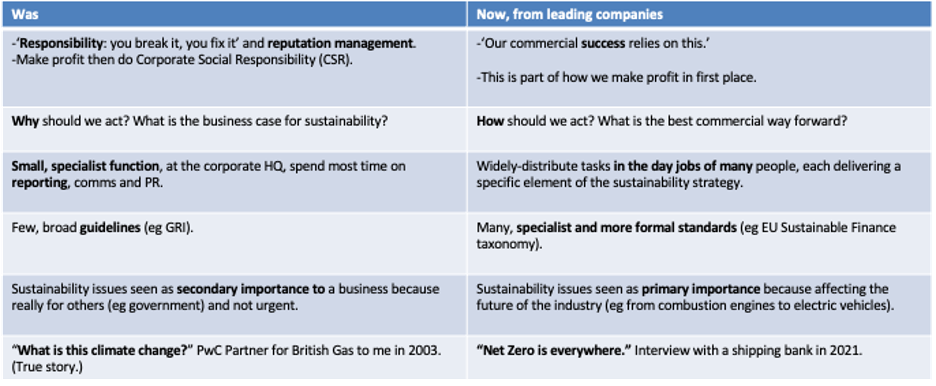

It is (mostly) summarised in these shifts David has seen since 2003:

Relating to the academic literature

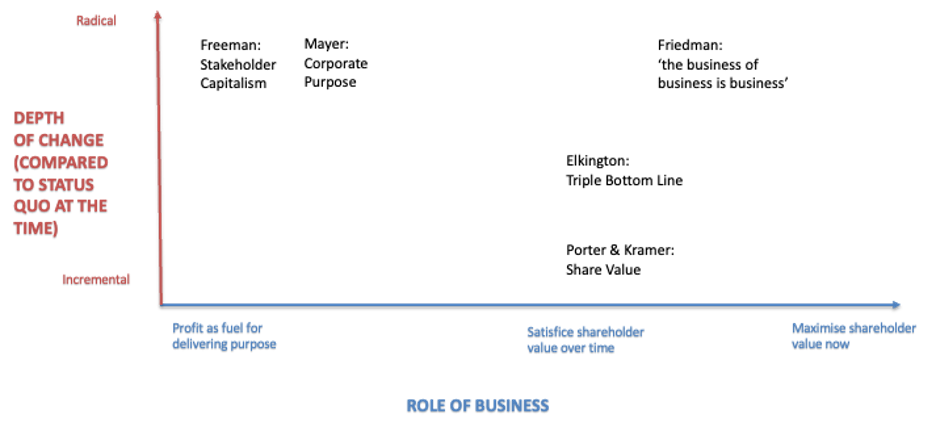

The second half of the lecture relates those experiences to the main parts of the academic literature:

Highlight: Stakeholder Capitalism

In our experience, the stakeholder capitalism perspective is the least understood, and so worth highlighting in this series.

What are we contrasting with?

Friedman’s claim that ‘the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits’ is so familiar that, for periods, it has felt like There Is No Alternative. John Elkington’s Triple Bottom Line has also been ubiquitous, even with the very public product recall in 2018. Strategy guru Michael Porter hardly needs any help to get Shared Value better known.

Mayer’s project in the British Academy on the Future of the Corporation is perhaps less known, but it’s findings – business isn’t just about profit maximisation but also solving problems which matter -- are deeply, deeply familiar (so much so that some of us wondered what took him so long, but that’s another story).

Background of stakeholder capitalism

There was a brief period in the mid-90s when stakeholder capitalism was in vogue. Readers of a certain age might remember it being advocated for in Will Hutton’s book The State We’re In. When opposition leader in 1996, Blair made speeches about creating a stakeholder economy, an ambition which was not kept explicit in office.

In the field of management, the key figure of stakeholder theory is generally identified as R Edward Freeman, who wrote ‘Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach’ in 1984. The core can be summarised as:

“Each person has the right to be treated, not as a means to some corporate end, but as an end in itself. If the modern corporation insists on treating others as means to an end, then at minimum they must agree to and hence participate (or choose not to participate) in the decisions to be used as such.”

Evan and Freeman (1988) in Jeffrey Moriarty,

The Connection Between Stakeholder Theory and Stakeholder Democracy 2012

The difference with shareholder capitalism

As such, the difference between shareholder capitalism (as advocated by Milton Friedman and a thousand MBAs) and Freeman’s stakeholder capitalism is power.

Building on Evan and Freeman (1988), in shareholder capitalism, ‘who benefits?’ are the shareholders and ‘who decides?’ is the board, acting in the interests of the shareholders.

In stakeholder capitalism, ‘who benefits?’ comes from balancing the interests of all the stakeholders and ‘who decides?’ follows from believing that all stakeholders should have the ability to participate in decisions which affect them.

Or, through a lens of class struggle, ‘who, whom?’, meaning -- who will dominate whom?

Some challenges of putting stakeholder capitalism into practice.

That said, one of the challenges of a stakeholder approach is on the level of practicalities. As a manager, I find it far easier to have one goal (returns to shareholders) and one decision-making group (the board).

Plus, I already know that a successful company does not simply ignore its stakeholders. I have to manage viable relationships with my suppliers, workers and customers. Their views influence me, even if I don’t give them a formal role in decision-making. Plus, there are known methods for all these activities, like customer satisfaction scores, and labour negotiations. Managing in shareholder capitalism does not require me to invent my management practices from scratch.

By comparison, the stakeholder capitalism is more complex, unfamiliar and, seemingly, immature. How can I balance all the interests of stakeholders? Does each group (employees, local communities, suppliers, customers, investors) count the same, or is a priority allowed? What is a good-enough level of participating in decision-making? If I am running a company under UK law, is there any conflict between my fiduciary duty (to act in the interests of the shareholders) and the stakeholder approach?

Other jurisdictions have found ways of integrating stakeholders. European countries have a long history of work councils. For instance, in Germany Betriebsräte have existed since the 1920s, and put on a strong footing in the 1950s. They serve two purposes: co-determination, electing members of the board; and participation, where they are consulted on formal issues. The UK has a rather different, and more combative, history of labour relations.

Stories from the UK context

Given the challenges of practicalities and power, it is no surprise that, at least in a UK context, the stakeholder-centric approach has been influential in bursts. As we’ve seen, there was a brief, but ultimately short, burst with the British centre-left of the 1990s.

Also, as discussed in unpacking David’s career [in the lecture but not in this highlight], in the UK the early 2000s was a time of ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ (or CSR), where the implicit assumption was business could continue as usual, with the added responsibility of reducing the damage of business-as-usual.

The main case for urgent action was reputation (‘do this, or campaigners will come after you!’). (Yes, there were other levers, including winning new customers, but these were less urgent and less top-of-mind for senior executives.) Therefore, a huge focus of CSR departments was communications and the annual CSR report.

Into that context, the main use of stakeholder theory was about who should be involved in creating those reports. Of course, being engaged in making a CSR report is already a significant dilution of Freeman’s proposition that all stakeholders participate in decisions that affect them.

Still, in the early 2000s that was what was realistically available. There was a time when some of the most important work in CSR was creating the standards and guidance for how to engage stakeholders in the reporting process, as codified Simon Zadek’s AccountAbility 1000.

As David explained earlier in the lecture [but not in this highlight], this CSR phase was rather superseded. Companies began to understand that these issues were not just about them effecting on others, but would also effect on businesses too. The focus shifted from the being responsible for impact on others, to being successful while being impacted upon.

As such, even if you only believe ‘the business of business is business’, you still needed to act to protect your future profits. Questions of responsibility turned into sustainability. For most large corporates, stakeholder engagement was limited to being a necessary part of creating a good sustainability strategy and report.

Cooperatives as a version of stakeholder capitalism.

There have been other legal forms for companies which do have formal roles for stakeholders who are not distant shareholders. The Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers was formed in 1884 as a consumers’ cooperative, where the customers own the business. This was an early, and pivotal, example. Many more cooperatives were formed, including, in the UK, building societies like Nationwide, shops like John Lewis and conglomerates like The Cooperative Group.

The fortunes of cooperatives have waxed and waned in the UK. The 1990s saw a wave of building societies becoming for-profit banks (a process known as ‘demutualisation’), reflecting the dominance the Friedman doctrine.

It is interesting to look at the list of demutualised building societies now, and see names like Northern Rock and Halifax. In shifting from owned by their customer to focusing on shareholder returns, many went from being rather boring building societies, to, at first, brilliant banks – before having to be rescued during the financial crisis of the late 2000s. (Meanwhile, those building societies which resisted the pull of demutualisation, did not need special treatment.) The incentives and priorities embedded in the legal form do seem to matter.

In Spain, the Mondragon Corporation is a federation of worker cooperatives and the leading business group in the Basque region. The companies in the federation come from a range of industries (finance, industrial, retail) and can be thought of as a cluster of stakeholder capitalism within the wider shareholder capitalism of Spain and the EU. While not perfect, it has a good record on how it treats its workforces, employing over 80,000 people in 2019. It is an example of a different economic model.

But, that doesn’t mean cooperatives are always a good thing.

During the years of CSR, in the early 2000s, The Cooperative Group was an acknowledged leader, and not just in reporting. It would set targets on environmental and social issues that would force other companies to catch up. It was a prime mover in initiatives like Fair Trade.

It had a rare governance set up, where people could become members, and from there get elected to local, regional and finally the national board. (They were known collectively as ‘Democrats’.) There was a time when this looked like a strength, and meant it was more grounded in doing good things for its customers and communities.

But it turned out to have significant shadow sides. First, the people elected up to the national board didn’t have the skills needed to guide an organisation with revenue in the hundreds of millions. They could not act as a brake on bad ideas.

The most important bad idea was that, as the largest cooperative, the Group was expected to act for the wider cooperative movement, and buy-up any smaller cooperatives that got into trouble. That meant it had a patchwork of different businesses, each of which elected people which then defended local autonomy. But retailers like Tesco were centralising, and vastly reducing their unit costs. The Cooperative shops became uncompetitive.

This all came to a head in 2014. The Cooperative Group looked like it might not be able to keep the terms of its agreements with bond holders (to whom it owed money). David was involved in facilitating a key meeting where the Democrats were asked to give up their governance roles, as a condition of a rescue package.

The broader points here, on all these stories:

- All forms (shareholder or stakeholder) have shadow-sides which need to be actively addressed.

- A failure of governance (who makes decisions and how they are made) is very often an important factor in why a business or organisation is failing.

Now in use with for-purpose business approaches

The last few years have seen the growth of the B Corp movement, an international network of organizations aiming for economic systems change. There are some 8,100 companies who are certified as For-Benefit (the ‘B’ in B Corp is ‘Benefit’) – meeting a minimum standard set by the B Corp core -- and with a growth of 63% in Europe in 2022.

To quote their own version of their history [emphasis added]:

“We began in 2006 with the idea that a different kind of economy was not only possible, but necessary — and that business could lead the way towards a new, stakeholder-driven model. B Lab became known for certifying B Corporations, which are companies that meet high standards of social and environmental performance, accountability, and transparency.”

Some of what Freeman meant by a stakeholder capitalism is being taken forward in the for-profit movement.

Where we are in the ten lectures

Introduction -- here

0. Situating the module’s perspective:

0.1 The only viable story of the future is transformation. -- here

0.2 Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level. – here

1.Business Responses to the Sustainability Crisis – this note.

- The recent history of ‘sustainable business’.

- Relating to the academic literature (including stakeholder capitalism).

2.Innovation Economics: Core Concepts and Issues (with a transformative lens).

3.New Product Development and Managing Technology Innovation.

4.(a) Sustainable Entrepreneurship and the route to commercialisation.

4.(b) Sustainable Finance.

5.Innovation (eco)system – beyond the cult of the entrepreneur.

6.Sustainable innovation in a digital age.

7.Sustainability Strategy and Scenario Planning.

8.Transitions and The Bigger Picture.

9.Public Policy for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation.

10.Exploring Innovation and Sustainability through a Case Study.