UCL Module: 3. New Product Development & managing technology innovation.

Managing technological innovation: Fuzzy front-end, New Product Development and Stage Gates. Profiting from innovation. Open innovation. Unexpected disruption. Dynamic capabilities.

This short SubStack series gives a weekly key insight from the Masters module I co-teach on 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business'. All those posts are gathered on this page. The Atelier of What's Next WeekNotes continue in parallel.

This week:

Overview of this lecture/chapter.

Innovation for sustainability in large and small firms.

Managing technological innovation: Fuzzy front-end, New Product Development and Stage Gates.

Profiting from innovation.

Open innovation.

Unexpected disruption—and how incumbents get surprised.

Strategic management and innovation: dynamic capabilities

Where we are in the ten lectures.

Overview of this lecture/chapter.

This post is on the third lecture. Previous posts covered the overall purpose of the module, the module’s foundational assumptions (the need for transformation; and, how every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level), the business responses to sustainability crises and, finally, core concepts and issues in innovation economics.

This post is concerned with how (mostly) large companies go about new product development and managing technology innovation.

(Again, this is one of the lectures that Will leads. You can tell because there are better references and more breadth. Consequently, also, this week, no deep dive.)

The lecture/chapter looks at different aspects of managing innovation, from the perspective of a larger company.

Innovation for sustainability in large and small firms

Sustainable transformation involves incumbents as well as new entrants.

From Hockerts, K. and Wüstenhagen, R., 2010 ‘Greening Goliaths versus emerging Davids’

There can be multiple routes to market for a product. One option is that a new firm both develops a technology and brings it to market.

But the other routes involve existing large firm, maybe only developing the technology, or only bringing to market a technology developed elsewhere, or, finally, doing both the technical development and bringing to market.

Adapted from Kirchberger, M.A. and Pohl, L., 2016. ‘Technology commercialization’

Managing technological innovation: Fuzzy front-end, New Product Development and Stage Gates

A large firm will have lots of activity in technological and product innovation. The mid-20th century was a heyday of corporate research laboratories. (Xerox’s PARC was foundational to been foundational to numerous revolutionary computer developments, like laser printing, Ethernet, the modern personal computer, the mouse and the desktop paradigm.) Even as those kinds of institutions have declined, large companies will have divisions and sub-groups covering research and development (R&D), innovation and commercialisation.

There are different ways to frame, and make all this activity easier to understand.

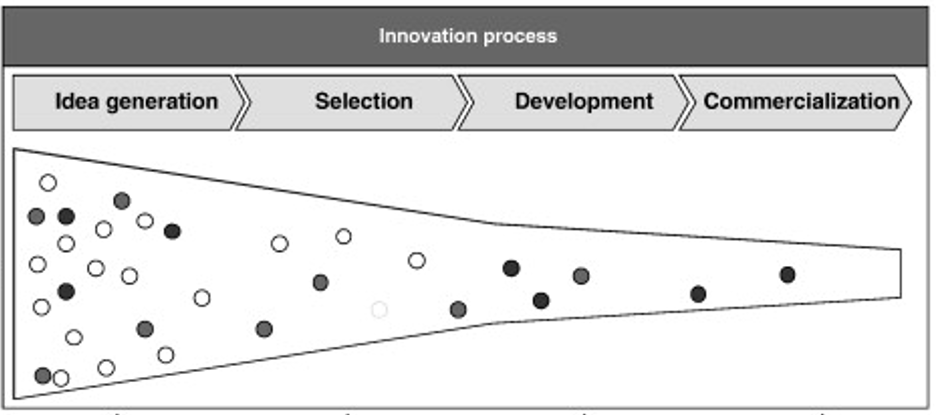

A well-known one is the Innovation funnel: the initial stage of idea generation is wide, and successively smaller numbers in selection, development and commercialisation.

Rohrbeck, R. and Gemünden, H.G., 2011. ‘Corporate foresight: Its three roles in enhancing the innovation capacity of a firm’.

Experience and research show that the early stages are key for a sustainability perspective. Much of the sustainability impact is determined by the basic idea, rather than the details of its development.

The idea generation at the ‘fuzzy front end’ can be from anywhere, internal and external. Bringing together possible customer needs with technology/product opportunities requires creativity, not bureaucratic procedures.

One practice is to screen ideas at key points, often known as Stage Gates (a registered trademark of Cooper). Unilever and Dow Chemicals use stage gates in their innovation process, for instance.

But innovation is rarely a linear journey. More like a spiral (with switchbacks) of accumulated knowledge, often needing to draw inputs and permissions from other departments (i.e. marketing, finance, manufacturing).

Many large companies have tried to graft sustainability into their existing innovation journey and formal process, for instance with specialists embedded in teams or with scored hurdles to jump over. For more in this, you can listen to the Innovation for Sustainability interview with Nicoletta Piccolrovazzi on her experiences at Dow Chemicals.

Not all innovation fits well with all these formalities, especially when trying to identify and nurture more radical ideas. There are a variety of strategies to address this, including: creating parallel project portfolios; having semi-independent ‘high risk innovation’ business units; monitoring the start-up landscape; and, looking beyond existing customers.

Profiting from innovation

But technological success does not automatically lead to commercial success.

Commercial strategy depends on many considerations, but three big ones:

- Complementary assets/capabilities: do you have the resources to commercialise and exploit the innovation?

- Business model: does your idea fit with the business model?

- Appropriability regime: how easy is it to capture the value of your innovation, rather than letting others benefit?

When it comes to securing value from knowledge there are three main routes:

1. First mover advantage (which is not always available).

2. Formal patent protection (like patents).

3. Secrecy and confidentiality agreements.

Open innovation

Open innovation builds on structured discovery, how it can be OK to give away your IP, and the importance of matching the business model to the innovation.

Instead of keeping all the activity within a company (‘closed’), a business can benefit from having more porous boundaries for ideas, activity and insight (‘open’). An open innovation approach allows a company to draw on expertise well beyond what its employees, and also innovations which might be too different from the existing business model to incubate within the firm.

Adapted from Chesbrough, H.W., 2003. Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology.

Digital technologies have made it easier to ‘unbundle’ tasks which used to be in the firm, as the outsourcing along supply chains shows. Open innovation has been carried by the same wave. Plus the greater mobility of workers, the greater complexity of products and the greater availability of venture capital.

Unexpected disruption—and how incumbents get surprised

New innovations are often disruptive. New and better goods or services can displace, even destroy, incumbents. Think of Kodak film or Blockbuster video.

Christensen’s Disruptive Innovation theory distinguishes between radical innovations (very different from before), sustaining innovations (which are adopted by incumbent firms) and disruptive innovations (which, eventually, undermine incumbents).

Incumbents focus on the needs of their most profitable customers, and tend to over-provide for them. New entrants can undercut with a worse, but cheaper, product, or serve new customers. At first the incumbent does not see the threat from this competition. But if the new entrant can grow customers, then they can improve their technology incrementally until it is good enough. Then they quickly take customers from the incumbents – who are too slow to react.

In the field of sustainability, it is possible that sharing economy innovations could benefit from these dynamics, as they are not good-enough for the over-served high-end market but could start out in low-end footholds. Also, un-served markets create niches for fostering clean innovation, such as off-grid PV.

Strategic management and innovation: dynamic capabilities

Firms can be contrasted in terms of their technological capabilities (such as: how skilled are their workers). Firms that succeed over long periods are those that are able to upgrade their capabilities continuously. Long-term performance of firms should be understood as depending on dynamic, rather than static, capabilities

Teece, D.J., 2007 has three dynamic capabilities in particular: “sensing” opportunities and threats; “seizing” opportunities; and, “managing threats”.

Where we are in the ten lectures

Introduction -- here

0. Situating the module’s perspective:

0.1 The only viable story of the future is transformation. -- here

0.2 Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level. – here

1.Business Responses to the Sustainability Crisis – here.

- The recent history of ‘sustainable business’.

- Relating to the academic literature (including stakeholder capitalism).

2.Innovation Economics: Core Concepts and Issues – here.

- What do we mean by innovation.

- Knowledge and intellectual property.

- Learning Processes.

- Technology and product live-cycles

- The diffusion of innovations

3.New Product Development and Managing Technology Innovation – this post.

- Innovation for sustainability in large and small firms

- Managing technological innovation: Fuzzy front-end, New Product Development and Stage Gates

- Profiting from innovation

- Open innovation

- Unexpected disruption—and how incumbents get surprised

- Strategic management and innovation: dynamic capabilities

4.(a) Sustainable Entrepreneurship and the route to commercialisation.

4.(b) Sustainable Finance.

5.Innovation (eco)system – beyond the cult of the entrepreneur.

6.Sustainable innovation in a digital age.

7.Sustainability Strategy and Scenario Planning.

8.Transitions and The Bigger Picture.

9.Public Policy for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation.

10.Exploring Innovation and Sustainability through a Case Study.