UCL Module 4.(b) Sustainable finance.

The three types of funding. What is a capital market? What, then, is sustainable finance? Real stories: finance system innovator; Green Bond Civil Servant; ethical investor; and two VCs.

This short SubStack series gives a weekly key insight from the Masters module I co-teach on 'Innovation and Sustainability in Business'. All those posts are gathered on this page. The Atelier of What's Next WeekNotes continue in parallel.

This week:

Overview of this lecture/chapter.

The three types of funding.

What is a capital market?

What, then, is sustainable finance?

Highlight: real stories around finance:

The finance system innovator

The Government Green Bond Civil Servant

The ethical investor.

The Deeptech ClimateTech VC

The Tech for Good VC.

Where we are in the ten lectures.

Overview of this lecture/chapter.

This post is on the second half of the fourth lecture.

Previous posts covered the overall purpose of the module, the module’s foundational assumptions (the need for transformation; and, how every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level), the business responses to sustainability crises and, core concepts and issues in innovation economics.

Then we looked at the organisational level. First, a post on how (mostly) large companies go about new product development and managing technology innovation. Last week, a post focuses on smaller and newer firms: entrepreneurship and the route to commercialisation.

This post looks at a new angle: sustainable finance.

The three types of funding for a business.

There are three ways which a company can fund itself: equity; loans; and revenues.

Equity. This is when a shareholder pays money into a business, and in return for owning a portion of the company. A shareholder has greater power than a lender, but is last in the queue for pay out if the company goes bust. The returns to a shareholder will be dividends (cash paid from this year’s profits after tax) and gains when selling the shares.

A company will sell new equity when it is wanting to create long-term assets (or dealing with long-term problems). Shares are also used as an incentive to staff.

Large companies’ shares are held by fund managers, who are investing on behalf of pension funds, insurers or others, and other institutional owners. Typically, a fund manager will own a tiny stake (say 0.1%) of a great number of corporations.

Small companies, like entrepreneurs, will have some different shareholders, including: founders; staff; and early investors (like Venture Capital funds). But far fewer than a large company, and each with a larger stake.

Loans. The company borrows money, and will pay regular interest plus return the amount of the loan (the ‘principle’) in the future. A lender has less rights than a shareholder, but might place covenants on the company, constraining what it can do.

A company might use a loan to finance create a long-term asset, but also to reduce its tax bill.

A company’s corporate tax is calculated after paying interest. So, the more interest you pay, the lower the corporate tax bill. But the regular interest payments are fixed, while the board can choose how much dividends to pay.

If you get all your funding from loans, and have one bad year, then you could go bust. If all from equity, you can decide to not pay a dividend instead, but your tax bill is higher in the good years.

The largest companies will have an entire Treasury department making sure they have the optimum level of loans to reduce their tax bill without increasing by too much the risk of defaulting on the loan or going bust.

Large companies will have a mix of commercial loans from banks and bonds. (Like a loan, the company receives and promises to pay regular interest and the principle back on a specific date. The difference is that those bonds can be traded, so the interest goes to whoever happens to be holding the bond on the date of payment.) Bonds are owned by fund managers and other institutional investors.

Smaller companies will just to have loans with banks.

Revenue. When a customer buys something that is funding the company.

When considering finance, it easy to forget revenue. Revenues pay for everything. All the costs of sales. All the operating costs. All the loan interest and repayment. All the dividends. All the shareholder value is based on the revenues being larger than costs.

Also most companies, especially large ones, fund their R&D and other internal investments out of retained earnings (past revenues less past costs).

What is a capital market?

Problem: Companies, governments and other organisations need cash now to create new assets. There are people and institutions who have cash now, and want more cash later.

Solution: capital markets. “A financial market in which long-term debt (over a year) or equity-backed securities are bought and sold, in contrast to a money market where short-term debt is bought and sold. Capital markets channel the wealth of savers to those who can put it to long-term productive use, such as companies or governments making long-term investments.” Wikipedia

Every capital market has:

Sell-side: Companies (and other organisations) who need cash to invest in assets.

Buy-side: Those with cash to put to use. The buy-side has many intermediaries, including: investment consultants; independent financial advisors, and fund managers.

A capital market like a stock exchange is an opportunity for sellers and buyers to find each other.

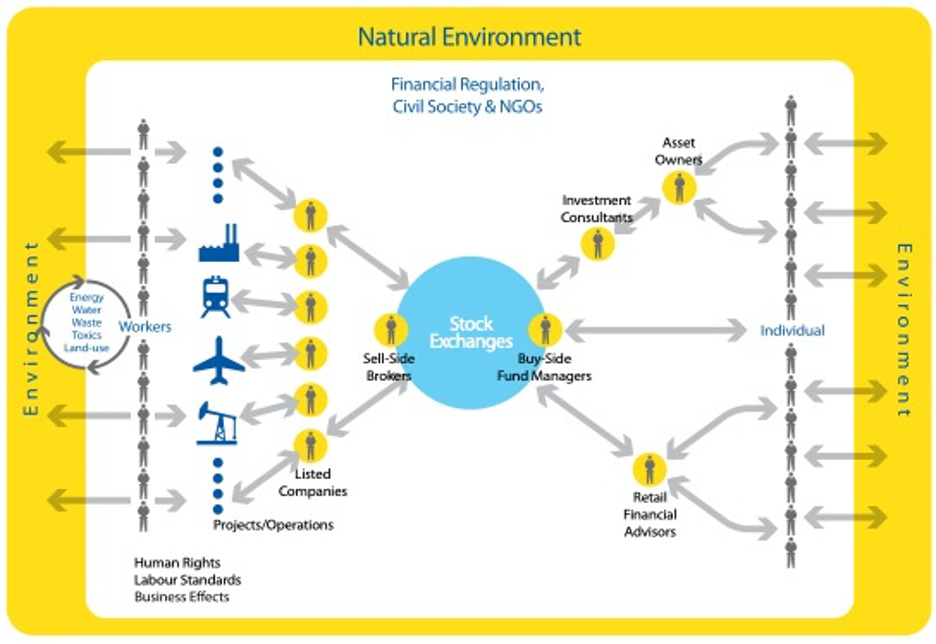

As we can see in this diagram from Aviva’s “A Roadmap for Sustainable Capital Markets” shows:

- The individuals with cash on the buy-side may also be workers in the companies on the sell-side. It is an irony that companies sack workers because of fund manager pressure, when those fund managers are acting on behalf of people have invested in pensions, namely some of those workers.

- All of the capital markets’ success relies on a functioning society and functioning natural environment. But capital markets have been blind (sometimes wilfully) to the effects of on society and the environment when chasing shareholder returns.

Another distinction worth knowing is public vs private markets.

Public markets. The financial instrument can be bought and sold easily by anyone registered with the trading market, for instance the London Stock Exchange. Such trading happens many times in the day. The trading is between institutional investors. No cash is going to the company. It can just see the price at which the shares (or bonds) are trading, and so be able to tell what investor sentiment is.

Private market. These are bespoke, one-off transactions which takes a lot of administration to happen and occur in private. For instance, when a VC fund invests in a startup, or when a small company is bought by a large one.

What, then, is sustainable finance?

Sustainable finance is a relatively new domain, still finding its feet. It is filled with obtuse jargon, which is contested and confusing. (There are times when David thinks the people in finance like how confusing the terms are to outsiders.) It is also dynamic and fast-changing. All of which means, the framings are contested and can age very quickly.

You can get a flavour of that in the European Commissions definition here:

“Sustainable finance refers to the process of taking environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into account when making investment decisions in the financial sector, leading to more long-term investments in sustainable economic activities and projects.

In the EU's policy context, sustainable finance is understood as finance to support economic growth while reducing pressures on the environment and taking into account social and governance aspects.

Sustainable finance also encompasses transparency when it comes to risks related to ESG factors that may have an impact on the financial system, and the mitigation of such risks through the appropriate governance of financial and corporate actors.”

Put another way, sustainable finance is all of the aspects in the previous sections – equity, loans and internal financing; capital markets, which can be public or private – but with some kind of sustainability lens.

Inevitably, there are different kinds of sustainability lens (using the Bridges Fund Management Spectrum of Capital):

Financial-only. Limited or no regard for environmental, social or governance (ESG) practices. Example: most mainstream investment opportunities.

Responsible. Mitigate risky ESG practices in order to protect value. Ethically- screened investment fund.

Sustainable. Adopt progressive ESG practices that may enhance value. Long-only public equity fund using deep integration of ESG to create additional value.

Impact, which has three sub-types, each with reduced priority for financial returns and increased priority for social and environmental impact:

Address societal challenges that generate competitive financial returns for investors. Publicly-listed fund dedicated to renewable energy projects.

Address societal challenges where returns are as yet unproven. Social Impact Bonds.

Address societal challenges that require a below-market financial return for investors. Unsecured debt to social enterprises.

Philanthropic (or Impact-only). Address societal challenges that cannot generate a financial return for investors. Charitable giving.

Note the over-use of neutral terms here. Does ‘financial-only’ investing really have no impact on sustainability issues? Or could ‘financial-only’ investing be what is supporting the status quo, and so be better thought as ‘negative impact’ investing?

It is hard to find up to date figures in public on the relative scale of sustainable finance. The general conclusion is that there is both fast growth of sustainable finance, and that it is still tiny compared to ‘finance-only’ and compared to what is needed.

For instance, The City UK, the industry-led body representing UK-based financial and related professional services has a report from 2022 which states:

“For example, green finance—using our definition—has grown rapidly from a low base, rising from $5.2bn in 2012 to $540.6bn in 2021. Nevertheless, it remains a very small part of overall financing activity, representing less than 2% of total finance (on a like-for-like basis) over 2012-21 cumulatively.”

Highlight: real stories around sustainable finance

Like last week, the best highlight is to focus on some real stories.

Over the last few years, the module has been accompanied by a podcast, ‘Innovation for Sustainability’, where David interviews practitioners to give students the grit under the fingernails of real experience (website, Apple, Spotify, elsewhere).

There are 20 episodes live at the time of writing (with 1 more recorded but not released). There have been over 5,000 downloads.

Here are the most relevant ones, with a little teaser of what we talk about.

The finance system innovator

The Government Green Bond Civil Servant

The ethical investor.

The Deeptech ClimateTech VC

The Tech for Good VC.

The finance system innovator

Steve Waygood is Chief Responsible Investment Officer at Aviva Investors (Steve’s corporate page and LinkedIn). He has been a crucial player in the rise of sustainable finance in the UK over the last 20 years.

The Government Green Bond Civil Servant

Jolyon Swinburn is a Senior Policy Analyst at The Treasury / Te Tai Ohanga in Aotearoa New Zealand (LinkedIn). The specific innovation which prompted the conversation was Jolyon working on Aotearoa New Zealand’s first green bond.

The ethical investor

James Corah (LinkedIn, Twitter) is Head of Sustainability at CCLA Investment Management, which exists to “help investors maximise their impact on society by harnessing the power of investment markets.”

The Deeptech ClimateTech VC

Beverley Gower-Jones is CEO of Carbon Limiting Technologies, which “works with industry and government to commercialise low carbon innovations and accelerate clean growth”.

The Tech for Good VC

Paul Miller (LinkedIn, personal website) is Managing Partner and CEO of Bethnal Green Ventures, which is “Europe’s leading early-stage tech for good VC”.

Our conversation covers how to run a ‘Tech for Good’ VC, including having a selection process that works, and investing in ambitious, leading-edge companies.

Where we are in the ten lectures

Introduction -- here

0. Situating the module’s perspective:

0.1 The only viable story of the future is transformation. -- here

0.2 Every approach to ‘sustainable business’ is innovation, at some level. – here

1.Business Responses to the Sustainability Crisis – here.

-The recent history of ‘sustainable business’.

-Relating to the academic literature (including stakeholder capitalism).

2.Innovation Economics: Core Concepts and Issues – here.

-What do we mean by innovation.

-Knowledge and intellectual property.

-Learning Processes.

-Technology and product live-cycles

-The diffusion of innovations

3.New Product Development and Managing Technology Innovation – here

-Innovation for sustainability in large and small firms.

-Managing technological innovation: Fuzzy front-end, New Product Development and Stage Gates.

-Profiting from innovation.

-Open innovation.

-Unexpected disruption—and how incumbents get surprised.

-Strategic management and innovation: dynamic capabilities

4.(a) Sustainable Entrepreneurship and the route to commercialisation – here.

-Steps in the entrepreneur journey.

-Not just the ‘heroic’ entrepreneur.

-What is different for sustainability-related entrepreneurs?

-The kinds of support in the ecosystem.

4.(b) Sustainable Finance. – this post

-The three types of funding.

-What is a capital market?

-What, then, is sustainable finance?

Still to come:

5.Innovation (eco)system – beyond the cult of the entrepreneur.

6.Sustainable innovation in a digital age.

7.Sustainability Strategy and Scenario Planning.

8.Transitions and The Bigger Picture.

9.Public Policy for Sustainability-Oriented Innovation.

10.Exploring Innovation and Sustainability through a Case Study.

Appendix: ‘innovation for Sustainability’ podcast episodes